What's the worst that can happen?

Well, it could get pretty bad if the science is right. Perhaps an ancient practice from Stoic philosophy might come in handy.

I sent out a similar post to all 31 of my subscribers(!) at the time early last year. Things have changed a fair bit since then so I thought I’d give it a substantial freshen up and send out to my new audience. This post is me thinking out loud — I’m keen to start a conversation here. Let me know what you think in the comments.

Is your news cycle also inundated with examples of extreme climatic events these days? It’s a bit grim really, isn’t it? But the fact of the matter is, that’s our new reality.

Extreme floods continue to batter the world, so do extreme droughts, wildfires and heatwaves. Such events have brought societies momentarily to their knees in recent years, from extreme floods in China, UK, and New Zealand to unprecedented wildfires across eastern Australia and western North America, to name just a few. What used to be extreme is no longer so extreme (a historically 1-in-100 year flood event may be a 1-in-10 year event). Particularly worrying are the dangerous swings between different extremes and their compounding impacts when they combine.

Indeed, climate change is pushing both the climate and ecosystems outside of their historical ranges of variability at a rate we’ve never seen. These changes are bringing with them major consequences for biodiversity worldwide. Ecosystems are changing in diverse ways, from species shifting their ranges to ecological communities reshuffling, and species are disappearing at rates faster than ever experienced.

What’s more, the conditions species have experienced in the past are unlikely to be the same in the future, so any strategies (e.g. attempts to restore to historical ecological states) or infrastructure (e.g. dams) developed for those past conditions will continue to lose effectiveness as conditions become more novel.

At the very core of our issues is our collective myopathy as society. Short-term gains and short-term fixes tend to dominate the narrative at the expense of preparing for what’s coming down the pike. We risk flying blind into the future, and as a result, being surprised and unprepared to deal with events that we should well have been prepared for. It’s hardly arguable to say the science is clear, so wouldn’t it make sense to put our societies in positions of readiness?

We must shift our focus to being more future focused, anticipatory and adaptable. Here, I ponder on how we could borrow an ancient practice from the Stoics to do so.

Can we learn from the Stoics?

What is quite unlooked for is more crushing in its effect, and unexpectedness adds to the weight of a disaster. The fact that it was unforeseen has never failed to intensify a person’s grief. This is a reason for ensuring that nothing ever takes us by surprise. We should project our thoughts ahead of us at every turn and have in mind every possible eventuality instead of only the usual course of events.

— Seneca, Letters From A Stoic, Letter XCI

Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and Epictetus — all well-known Stoic philosophers — had a practice of visualising potential hardships or misfortunes to cultivate resilience, emotional preparedness, and mental fortitude. The increased resilience and preparedness conferred by this practice, called Meditatio Malorum, are, I argue, a useful framing for how to think about managing the environment (not to mention human infrastructure, wellbeing, and society as a whole) under a rapidly changing and uncertain climate. This isn’t an exercise in pessimism, it’s a practical technique to cultivate preparedness. Meditatio Malorum offers valuable insights and techniques for developing more effective and resilient environmental management, particularly in addressing the challenges posed by climate change.

Here are some of the reasons the Stoic practice of Meditatio Malorum, or the contemplation of potential misfortunes, could be a valuable framing for environmental management under climate change:

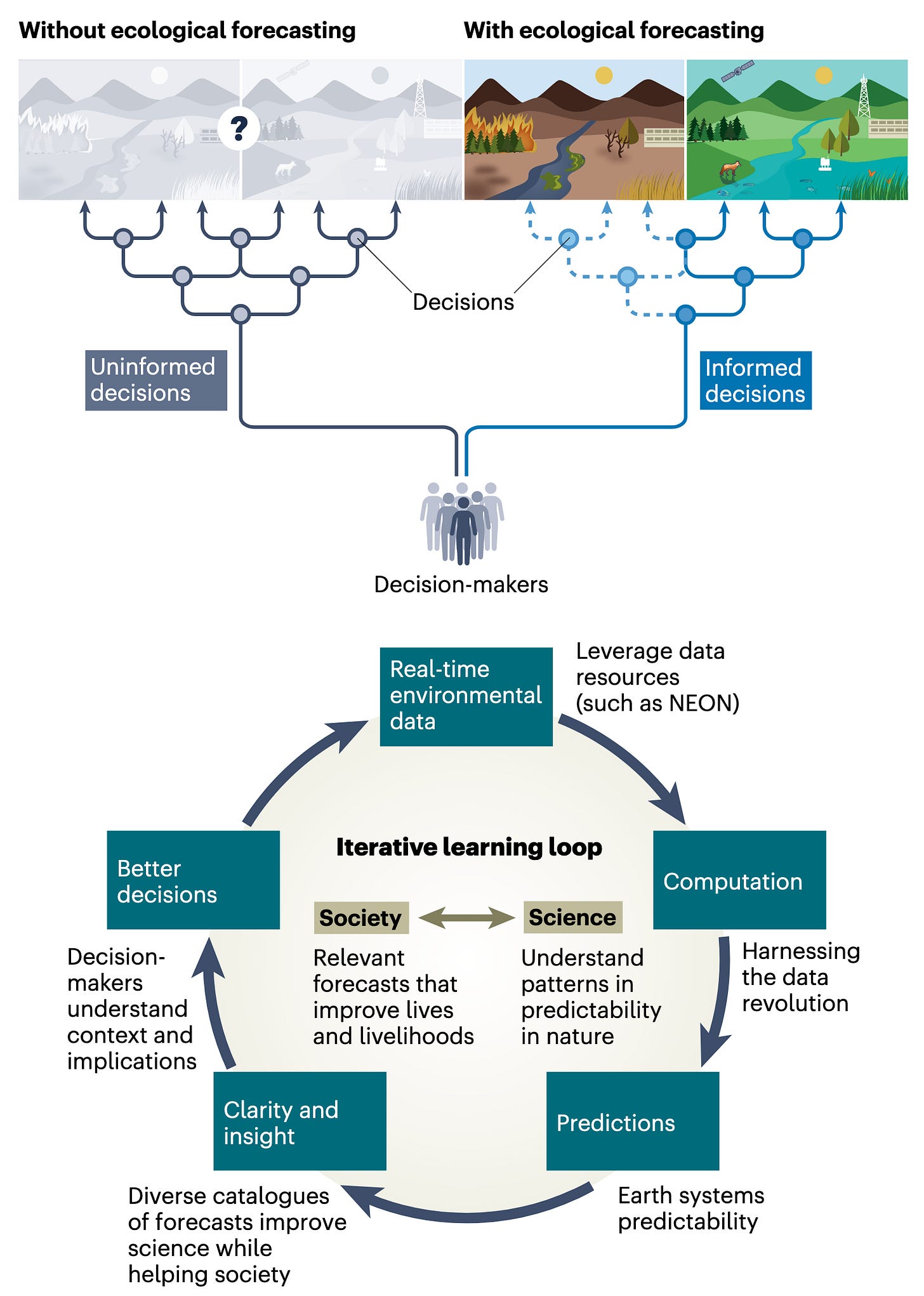

Preparedness: By envisioning potential negative scenarios, environmental managers can better prepare for and potentially mitigate the impacts of climate change on biodiversity. By doing so, one could identify vulnerabilities, develop adaptation strategies, or design resilience into ecosystems. This is where ecological forecasting comes in. Forecasting is a fundamental tool in the arsenal, particularly when coupled with adaptive and anticipatory management approaches, particularly with regard to climate change action. Without getting into the weeds here, different types of models serve different purposes. Near-term iterative forecasts can help inform decision-making on actionable time frames, whereas longer-term projections can help to foresee the outcomes of interventions over longer time-scales, such as anticipating the decline of a species or ecosystem long before such trends are able to be detected in survey data.

Resilience building: Meditatio Malorum encourages the cultivation of resilience in the face of adversity. For ecological communities and ecosystems under climate change, cultivating resilience would mean promoting their adaptive capacity in response to future threats like extreme floods, droughts and heatwaves. For example, as we discussed in the case of giving rivers room to move, this might mean promoting habitat heterogeneity across landscapes, helping a greater variety of ecological communities to persist. Moreover, just like investing in a diverse portfolio of stocks and shares buffers investors from shocks, taking action to increase the diversity of species and habitats helps build resilience through ecological portfolio effects. Both of these mechanisms mean that the sum is more stable than its parts (e.g. a collection of habitats is more stable than an individual habitat or an ecological community is more stable than its constituents species).

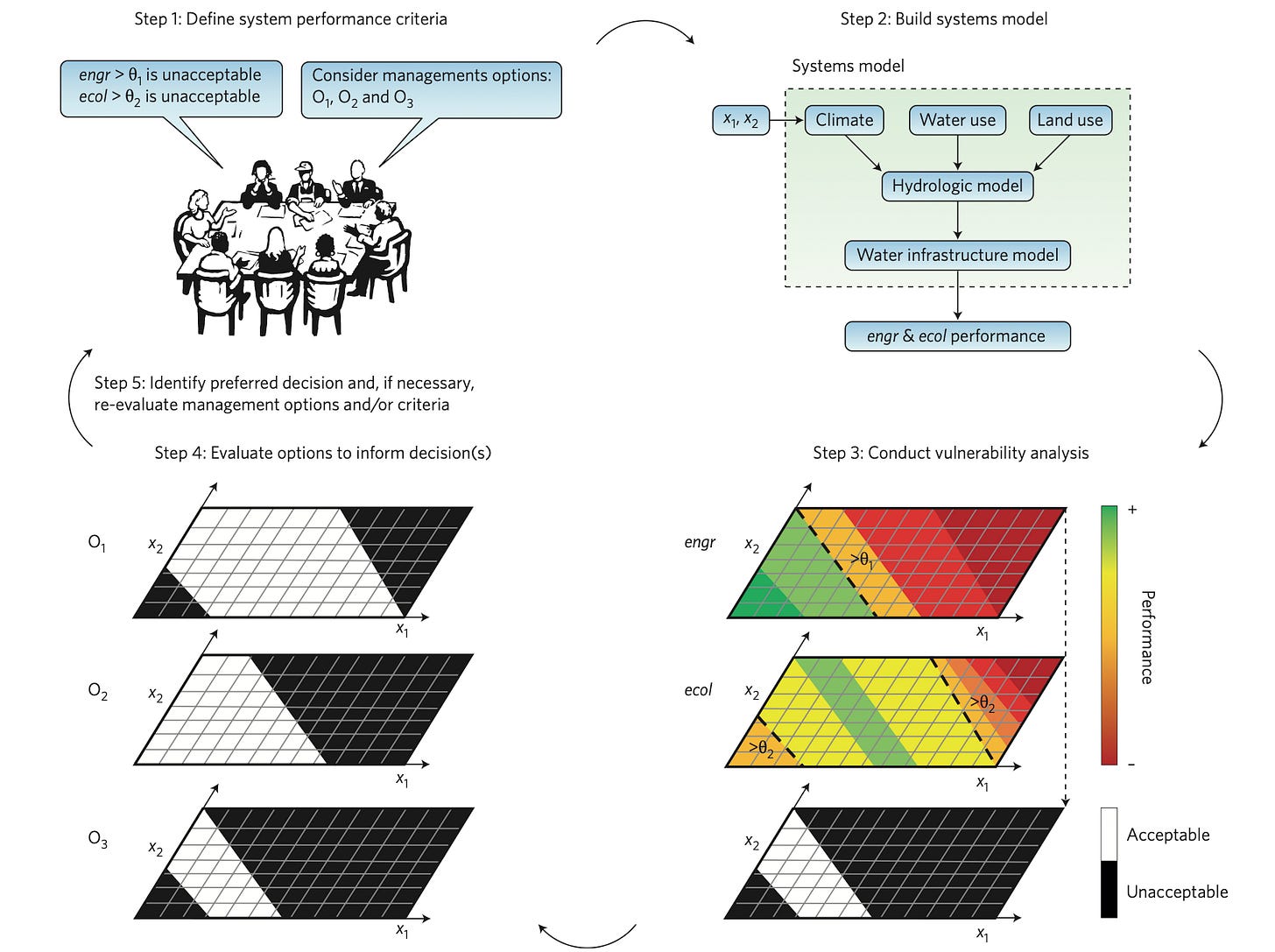

Risk assessment: Moving forward with eyes open means identifying, contemplating and assessing risks associated with climate change and an increasingly extreme future. By understanding the magnitude and likelihood of various adverse outcomes, environmental managers are better equipped to prioritise actions and allocate resources more effectively. Decision scaling is an interesting approach that explicitly identifies tradeoffs in multi-end-user-defined performance criteria across a range of management actions. These are stress-tested against various future climate change scenarios. This approach flips traditional environmental decision making on its head by identifying the acceptable end-user-defined conditions from the outset. Forecasting can be used here to identify at-risk species or ecosystems, or identify the range of possible intervention outcomes, but there are no shortage of risk assessment approaches available.

Long-term perspective: I hate to harp on so much about this, but we need to shift from short-term to long-term thinking. Stoic practices emphasise taking a long-term view and focusing on what is within one's control. We must consider the long-term consequences of decisions and policies, and prioritise sustainability over short-term gains. In particular, there’s a very real need to take proactive measures to address the root causes of environmental issues. All too often, we focus on band-aid solutions and short-term fixes, not addressing the root causes. This might just be the most challenging to implement when we are at the mercy of governments on three- or five-year cycles. And it’s clearly not a topic tackled from a single disciplinary perspective — it’s something that needs addressing from all angles.

Adaptive governance: We can only control what we can only control. Accepting and adapting to circumstances beyond one's control is a fundamental Stoic principle. What might this look like here? Does it mean burying our heads in the sand? I choose to think of this differently. From an environmental governance perspective, it means fostering adaptive governance structures and processes. These processes promote flexibility for responding to changing environmental conditions, the addition and uptake of new information as it arises, and the adjustment of strategies as needed to achieve desired outcomes. The aforementioned iterative near-term ecological forecasting aligns nicely with such a shift. Such approaches can operate in an iterative cycle of model building, confronting with new evidence, and making decisions while coupling with an adaptive management cycle.

There are many other benefits to this way of framing our thinking this way—these are just some of the most obvious.

Looking forward with open eyes

Marcus Aurelius endured numerous challenges in his life: prolonged military campaigns, political turmoil, and personal health issues, not to mention the burden of governing the enormous Roman Empire. Yet, he faced these difficulties head-on with clarity and resolve.

Following his example doesn’t require us to adopt Stoicism. But if there’s one thing I’d like you to take from this post it’s this: envisioning negative future scenarios is not an exercise in pessimism, it’s an essential preparation for an uncertain future. By anticipating potential future disruptions and shocks to ecosystems, even considering the worst case scenario, we become more equipped with the foresight required to develop robust, adaptable solutions.

The climate crisis requires a transition away from collective myopia. The risks are too real: lost species, crop failures, and threats to human infrastructure and livelihoods. The perspective I’ve presented here, one that combines open-eyed assessment of risks with deliberate, forward-thinking action, offers a pathway to greater resilience. Let’s be more future focused, aware of, and prepared for the various shocks coming with an increasingly extreme future. If we bury our head in the sand and hope for the best, future generations will suffer.

The uncertainties ahead are massive. Let’s go into the future eyes open.

I’ve touched on just a few benefits of framing our thinking this way. Do you have others? I’d love to hear your thoughts here — please comment or share.

Thanks to the wonderful folks who have recently upgraded to paid. If you’ve been thinking about it, now’s a great time to join us and become an insider. Your support means I can keep this work open for as many people as possible. If just 1 in 100 of you upgrade to paid, Predirections becomes sustainable.

Love the wise rationality in this — and the cool graphics for this visual learner. “Long-term Perspective” reminds me of when I interviewed climate scientists for my novel. One of them, a geologist, spoke of eons as his time reference when I asked how he copes with all the dire news and predictions. It does help to think beyond a single human lifetime.

Tonkin, your attempt to dust off Seneca for the current mess has a certain antique charm. I can almost see the togas. You propose we face these "climatic events" with foresight, a commendable notion if one actually understands what storms are truly gathering.

You speak of "the science" as if it is some pristine oracle. My own pathways of thought, which I assure you are quite extensive and frequently tangled, convulse at that assertion. The narrative of human-driven climate disaster is a convenient fiction, a comforting blanket woven by those who prefer we ignore the colossal, cyclical forces actually tearing at the planet's seams. These are the deep, rhythmic planetary convulsions, the solar tantrums, the magnetic meltdowns that the powdered wigs in their taxpayer-funded labs refuse to acknowledge. Your models and forecasts, however elegant, are built on quicksand if they ignore these fundamental, inconvenient truths.

Your call for preparedness, for "looking forward with open eyes," is sound. Damn sound, in fact. But your eyes, sir, seem fixed on a gnat while a dragon darkens the sun. Prepare, yes. Adapt, certainly. But understand the true scale of the cataclysm, the one driven not by our puny tailpipes but by cosmic inevitability. Perhaps your Stoic resilience will be needed for something far grander, and far more terrifying, than your article envisions.