Boom-and-bust or should I say bloom-and-burn?

Hydroclimate volatility is increasing. Los Angeles is just the tip of the iceberg.

We've all seen it but didn't have a name for it. One year, you're being battered by massive rainfall and flooding events, the next by a prolonged drought followed by devastating wildfires.

California is a poster child for these wild swings over recent years. After a long period of drought, 2022-23 saw nine atmospheric rivers hammer the state in three weeks – record-breaking precipitation resulting in widespread flooding and landslides, with disasters declared in 40 of the state’s 58 counties.

2023-24 continued this trend for the southern part of the state. Such conditions result in a massive build up in new vegetation such as grass and brush, which, when faced with prolonged drought and heatwave conditions (as have played out through 2024 and into early 2025), can become tinder dry, fuelling the flames of devastating wildfires.

And here we are. Los Angeles is burning with devastating force. And it's just one more example of what a new paper is terming "hydroclimate whiplash" – rapid swings between intensely wet and dangerously dry weather.

We all knew extreme events were increasing in frequency and magnitude, and expected to increase with continued climate change. I've discussed extreme floods before in this newsletter, for instance. But it seems we need to consider how they link together as this is when they can be particularly devastating. It's not just the isolated floods and droughts we need to be concerned about but it’s the dangerous swings between them.

I've talked before about my concern around compounding extremes (back-to-back events that can have greater impact than standalone events), but these whiplash events are a particular form of event that tend to happen in cycles. They might include "bloom-and-burn" cycles, where vegetation is overwatered followed by overdrying or it might be landslides that occur during rainfall that follows fires, where the soil/plant-root infrastructure has been damaged, for instance. An analogy can be made to New Zealand's problem with landslides following pine plantation clearance.

The paper, led by UCLA's Daniel Swain, synthesises knowledge of hydroclimate volatility in the context of climate change, including defining a metric of hydroclimate whiplash to identify the trends of such events across the world. It’s actually not a new phenomenon, but the paper sheds new light on it, bringing together the research out there and synthesising the trends.

Swain, D. L., A. F. Prein, J. T. Abatzoglou, C. M. Albano, M. Brunner, N. S. Diffenbaugh, D. Singh, C. B. Skinner, and D. Touma. 2025. Hydroclimate volatility on a warming Earth. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 6:35–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-024-00624-zSimilar wet-to-dry or dry-to-wet transitions have been widely documented in eastern Australia over recent years. Australia jumped from the massive Black Summer fires to a three-year period very wet La Niña weather systems.

These have caused widespread human health impacts, threats to public safety, food and water security issues, and losses of infrastructure. And the paper identifies many more examples from across the world in recent years.

For instance, torrential rains during the 2023 autumn harvest season in eastern Africa destroyed thousands of hectares of crops and displaced two million people. These events followed five consecutive years of drought, which resulted in food insecurity for over 20 million people.

The study finds that these hydroclimate whiplash events have already increased globally by 31% to 66% since the mid-20th century, more than what climate models suggest they should have.

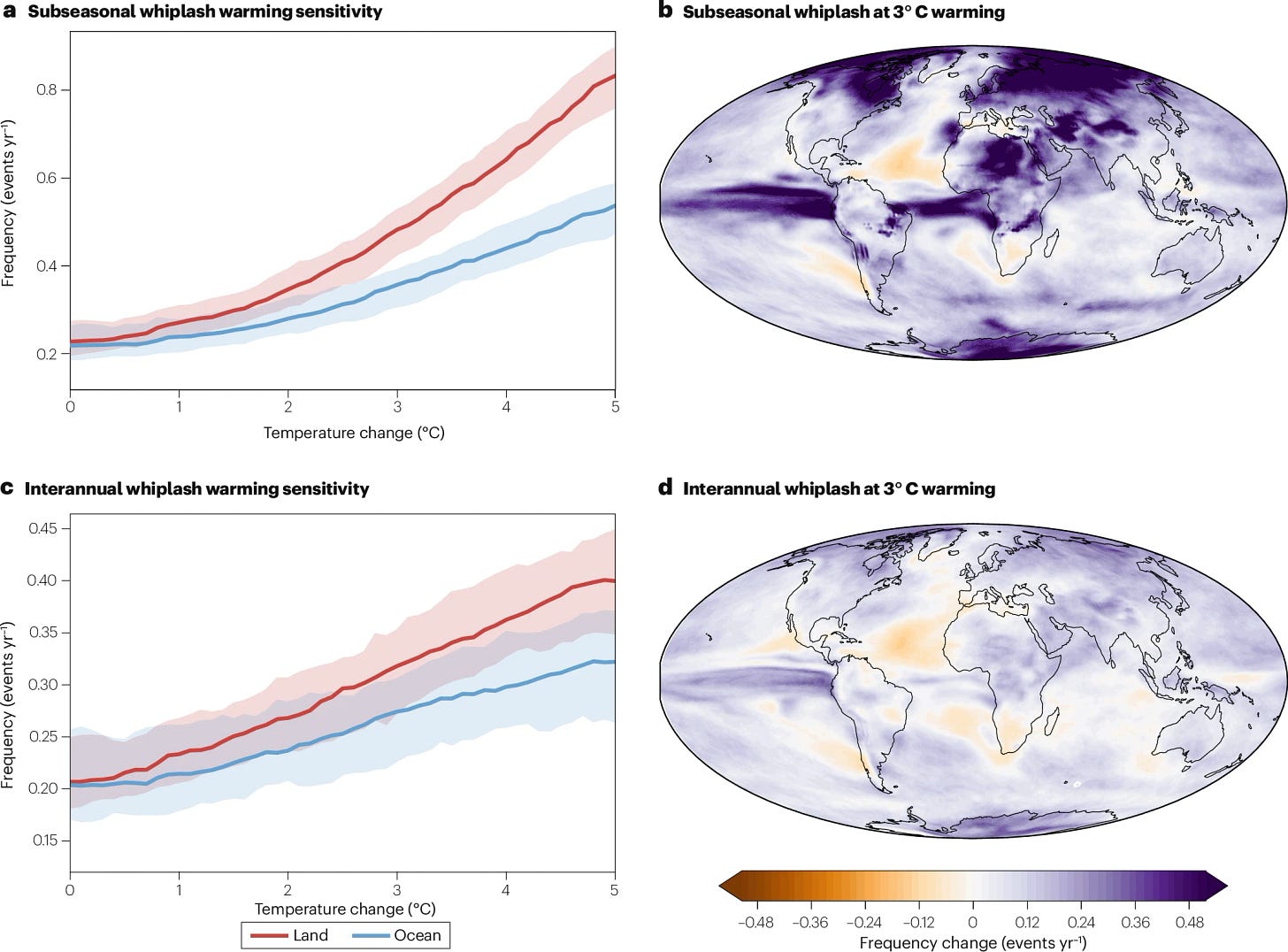

Even more concerning is that they are projected to increase with increasing climate change. And the frequency is projected to increase more on land than in the ocean.

But what is the key driver? Well, it’s the fact that a warmer world is just more forceful when it comes to the climate. For every degree (in Celsius) of warming, the atmosphere's ability to evaporate, absorb and release water increases by 7%. That is, there are "nonlinear increases in the water holding and water evaporating potential of the atmosphere".

“The problem is that the sponge grows exponentially, like compound interest in a bank,” the study's lead author, Daniel Swain said. “The rate of expansion increases with each fraction of a degree of warming.”

What is concerning with these events is not just the precipitation or lack thereof but the fact the atmosphere is thirstier, amplifying drought by increasing the force by which moisture is sucked out of plants and soil.

The consequences are huge, and the distribution of threats is unequal. High latitudes and eastwards from northern Africa to South Asia appear particularly vulnerable to increasing hydroclimate volatility.

I've talked already about the impacts of extremes on ecosystems. But this volatility will further amplify the impacts of floods, droughts and associated wildfires, and landslides on ecosystems and people alike. Hydroclimate volatility will increase disease risk too by allowing rapid growth of populations of disease vectors such as mosquitoes.

It will threaten food security for billions of people due to crop failures, and it will threaten lives through the direct impacts of cascading extremes, such as rainfall-induced landslides that follow wildfire events.

So, it seems we can't just focus on managing for increasing one-off extremes. The climate is becoming more erratic. Massive pulses of water are hugely problematic for human livelihoods, infrastructure, biodiversity, but so too are the increasingly drier periods in between. Instead, we need to co-manage these events as a system to avoid the worst consequences.

Every fraction of a degree of warming counts. So, of course, the best thing we can do is limit warming. And the best way we can do that is to rapidly and drastically phase out fossil fuels. But there are other things we can do, including prioritising sensible natural climate solutions in both forests and non-forest ecosystems.

This is scary stuff, I know. But it's important to be aware of these threats so we can manage them accordingly.

Feel free to click the ❤️ button on this post to help more people discover it. Tell me what you think in the comments! And please do share away.

Hydroclimate whiplash is such a perfect term. Your post is a nice expansion on this Axios article, which mentioned Swain and his research in regards to the LA fires: https://www.axios.com/2025/01/12/la-fires-climate-change-drought-extreme-weather

Like you say, we have all lived through "boom and bust" weather cycles with water. We just didn't have a "fancy" term for them. "Hydroclimate Whiplash" isn't bad and conveys clearly that this is NOT a "good thing".

I thought it was interesting that they looked at +3°C of warming. Particularly considering that +3°C over baseline is now acknowledged by ALL of the factions in Climate Science as "inevitable".

The Moderates think the Rate of Warming is around +0.25°C/decade and we will reach +3°C around 2080. UNLESS we reach "net zero". They THEORIZE that warming will basically stop at that point at whatever temperature we have climbed to.

Hansen puts the RoW at around +0.32°C/decade. He forecasts +3°C between 2065 and 2070.

I think the RoW is going to be around +0.4°C/decade. I am forecasting +2°C between 2030 and 2035 with +3°C happening between 2055 and 2065 depending on accelerating feedbacks.

EVERYONE in Climate Science thinks +3°C this century is going to happen.

From the looks of these Hydroclimate Whiplash forecasts it's going to be a VERY different planet. One that's much, MUCH hungrier.

From the paper:

"At the global scale, 60% of land area is projected to experience accelerated transitions between dry and wet periods under a high warming scenario."

"The magnitude of these changes depends on the metric, method and warming scenario, but there are suggestions of 2.5× increases in globally averaged subseasonal precipitation whiplash and 5× increases in interannual dry-to-wet events over global land areas compared with the historical period."

"Additionally, hydrologically intense years are further projected to triple in major global river basins even under moderate warming".