How many more species will we let disappear?

Extinctions will accelerate rapidly if global temperatures continue to rise.

Old Blue was the last breeding female of her species, the black robin, back in the 1970s.

Old Blue, as she was affectionately named based on the blue tag on her leg, is a symbol of resilience and of the remarkable power of conservation to save species on the brink of extinction.

Due to the arrival of rats and cats following human settlement, her species was down to seven individuals on the Chatham Islands (Little Mangere Island to be precise), a small set of windswept, rugged islands approximately 800 km to the east of New Zealand. But thanks to her and the work of conservationists, who cross-fostered eggs and young to another species, the population now sits somewhere around 300 individuals.

Admittedly, this may be one of the, if not the, most famous cases of conservation saving species on the brink of extinction. But there are countless other examples of hugely intensive conservation efforts doing similar things.

Conservationists have worked so hard to limit the damage that humans have wrought on species around the world. Many times these extinctions or extinction risks are primarily driven by invasive species, but over harvesting, habitat loss and other stressors are in the mix of drivers. New Zealand alone has several examples of species that would be extinct without the help of time-consuming and costly interventions, including converting a whole suite of offshore islands into predator-free reserves.

But what happens with something that operates on a much larger scale like climate change?

Well, we’re yet to find out (but see below for some evidence).

Climate change presents a much more challenging and insidious problem to deal with and will affect the entire globe. Even places that are free from human impacts are at risk.

Consider an alpine plant that has evolved over millennia to specialise on a particular microclimate or a bird that specialises on feeding on that alpine plant’s berries. As temperatures rise, their microclimate moves uphill. But they can only go so far before they hit the summit and run out of space.

In streams, low mountain ranges may act as summit traps where cold-adapted species eventually run out of room to respond to ongoing warming. Models have highlighted these as particularly problematic in climate projections across Europe.

Climate change extinctions

A recent paper from Mark Urban (whose work I have an enormous amount of respect for and has influenced mine a lot) shows just how much trouble we're in.1

Yes, we've been studying extinction risk for decades. So what more can one do in this space, you say? Well, you can analyse the analyses. Huh?

Using a technique widely employed in medicine (and ecology for that matter), he analysed the outputs of hundreds of existing studies. Individual researchers can examine extinction risk of one or a few species locally, but getting a handle on global extinction risk for all species? Well that requires syntheses of many studies, like Urban has done.

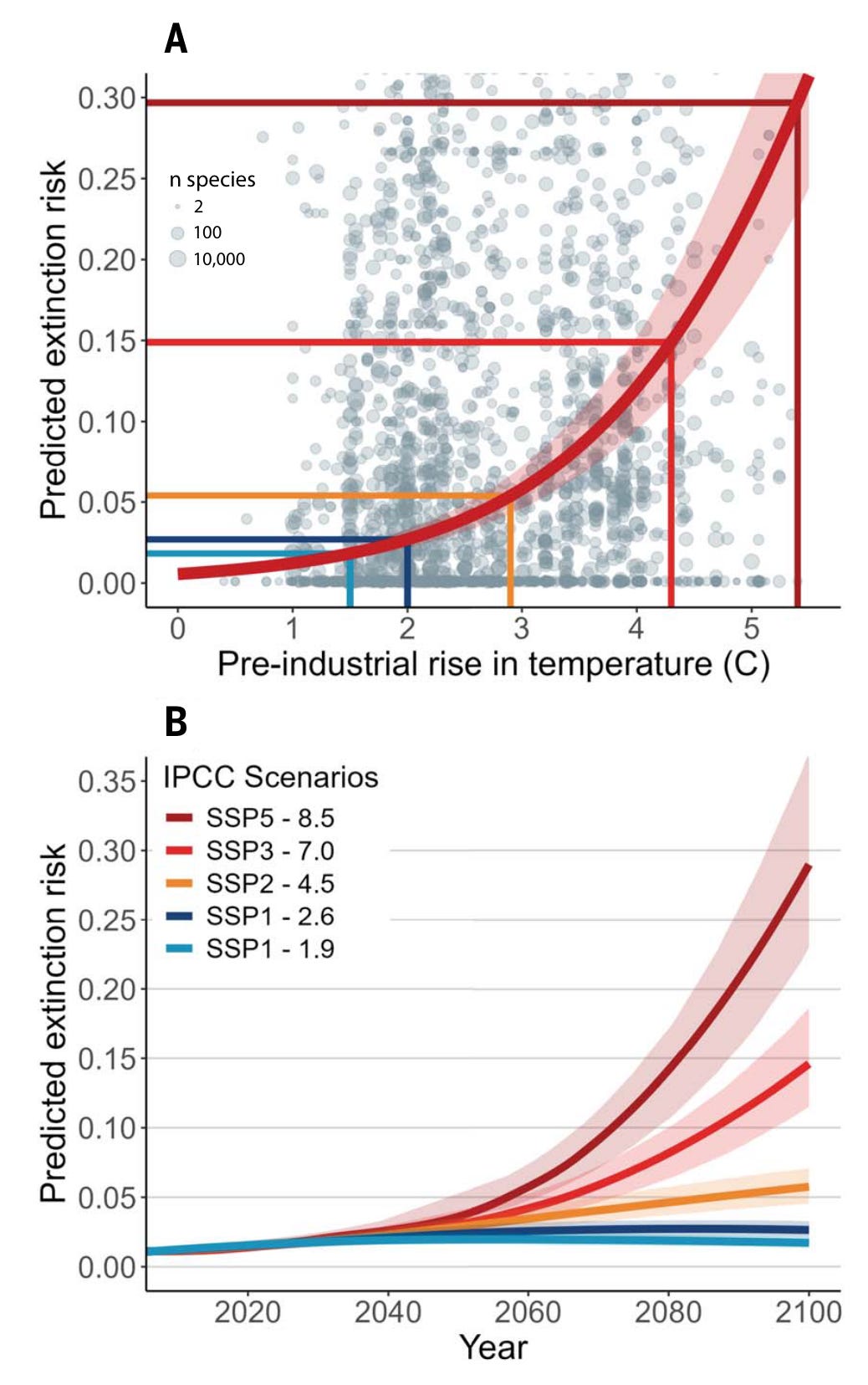

In an enormous amount of work, he synthesised 485 studies and more than 5 million computer model projections to examine the risk of climate change extinctions globally. He demonstrated that rising temperatures will lead to an increasing number of extinctions. Under the highest emission scenario nearly a third of the Earth’s species are predicted to go extinct.

His results are stark, showing that extinctions will accelerate rapidly if global temperatures exceed 1.5°C. The more extreme climate change, the more species will go extinct, but these extinctions are biased to certain regions and species. At particular risk are "amphibians; species from mountain, island, and freshwater ecosystems; and species inhabiting South America, Australia, and New Zealand."

From an Aotearoa New Zealand perspective, it’s particularly concerning is that NZ is one of those high-risk regions. But it is difficult to know without further in-depth analysis of the paper how many NZ studies are actually included in the study as NZ studies were lumped together with Australian. Australia and NZ have very different native biodiversity and are subject to very different pressures from climate change, particularly related to changing frequencies and magnitudes of extreme climatic events. But these are the sorts of generalisations that are hard to avoid in such global studies.

How can we let extinctions happen, even when we know what’s coming? Each of these species is here as a result of millions of years of evolution. They've experienced and encountered so many challenges over the millennia and yet have survived to be here despite these challenges. But our footprint on the planet is leading to their disappearance in mere decades.

This speaks volumes about our collective shortsightedness.

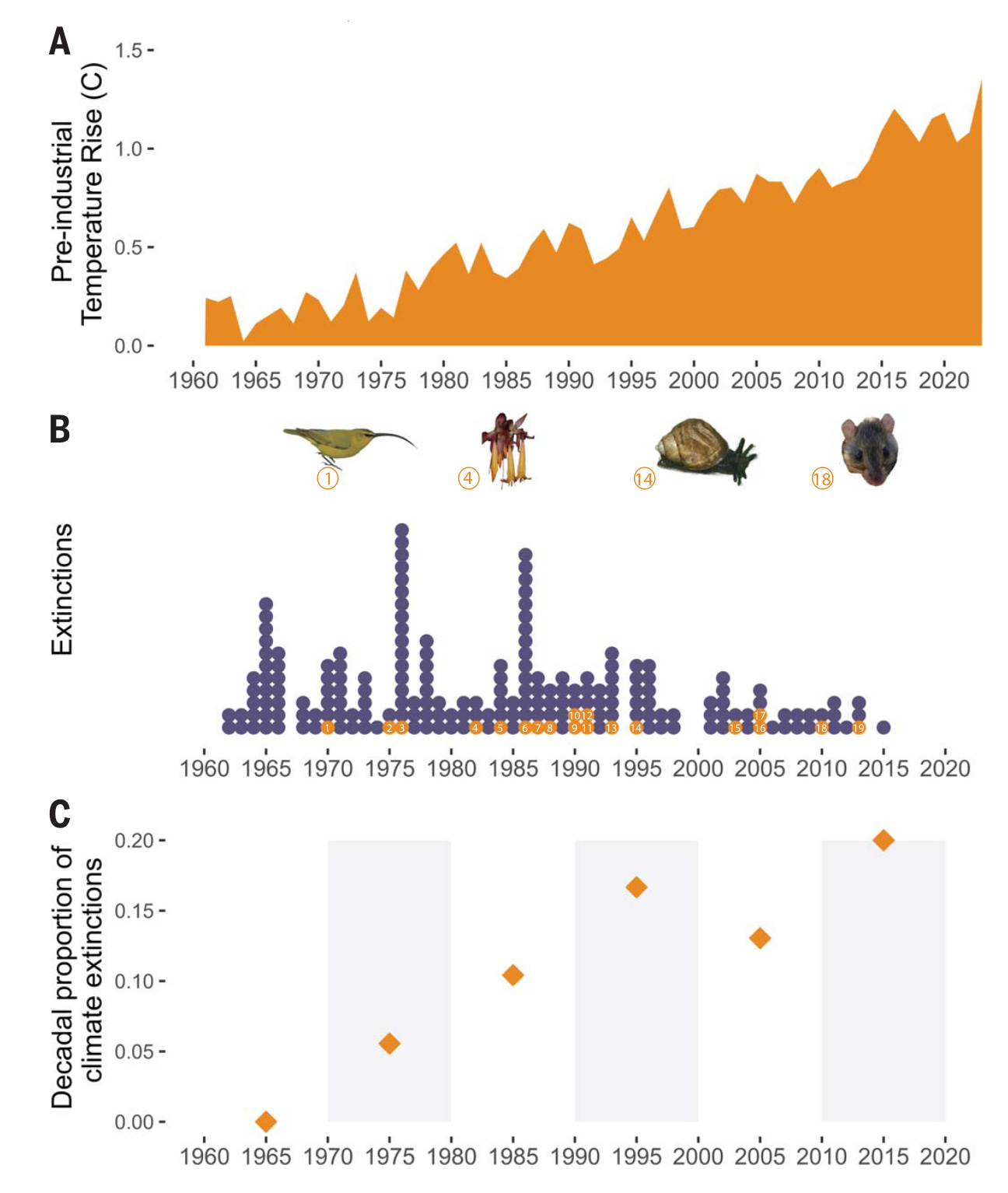

Climate change has already contributed to an increasing proportion of observed global extinctions in recent decades. To be precise, 19 extinctions have been attributed, at least in part, to climate change. Matching the study’s predictions of future at-risk species, most of these have involved species from island, mountain, and freshwater ecosystems.

However, so far climate change has played a subordinate role in extinctions compared to more traditional stressors like habitat loss and invasive species. The key point, though, is that climate change can impact species in places far from human impacts. And as climate change accelerates, so too will the risk of climate change-drive extinctions.

Finally, a note on the approach used in the paper: the results are dependent on the underlying studies that have been summarised. A large proportion of the studies underlying this meta-analysis are based on approaches that associate species’ current ranges with climate variables and then extrapolate these forward. These often miss the nuances associated with changing climatic variability, particularly related to extreme events like droughts, floods, and heatwaves.

Most of these models also miss important impacts like co-extinctions, which can hugely increase rates of extinctions. One study suggests co-extinctions may increase the effect of primary extinctions of vertebrates by more than 180%.

So the results could be heavily underestimating the risks many species face. Urban found that adding more realism into models (through using mechanistic rather than correlational models) with advances that have come in recent years can change the predicted risks.

Nonetheless, even with the broad, sweeping nature of the study, the results are extremely concerning. And as Urban states, these predictions are a lower bound, with predicted risks likely to increase as we continue to uncover hidden biodiversity around the world.

Conclusions

As I said in a recent note:

Biodiversity loss is a climate change multiplier. Every species we lose, every ecosystem we destroy weakens the planet’s resilience capacity.

Diverse forests store more carbon than monocultures. They're also more resilient to extreme weather events. Even soil biodiversity determines how much carbon remains locked underground rather than in our atmosphere.

Biodiversity isn't just a nice-to-have, it's a must-have. For all of us.

I've talked at length in the past about the need to tackle climate change and biodiversity together. And of the importance of diversity for a variety of reasons, including resilience to extreme events and unknown future shocks. Each species we lose erodes this resilience.

So, what can we do?

Well, if countries met the target of not surpassing 1.5°C, only 1.8% of species will be at risk of extinction by the end of the century. This is already bad enough but it's a lot less bad than exceeding it. Any more and the outcomes will likely be catastrophic.

One of the key focuses on stopping extinctions to date has been through protected areas and protecting habitats. While still fundamentally important, this may not be enough in the future. Limiting warming is critical Active and targeted conservation efforts will obviously help to plug the leak but reducing emissions has to come first. However, it will remain important to pinpoint key at-risk species to prioritise immediate conservation efforts.

As is all too often the case, we know what to do, but we aren’t doing it fast enough.

Finally, I realise I've written a couple of posts in a row more focused on impacts rather than solutions, so I might try to turn things a little more positive next week.

Thanks for reading!

Predirections thrives through the support of our paid members. If you value these insights and want to sustain this work, please consider upgrading. Your subscription ensures I can dedicate the necessary time to create thoughtful content while keeping Predirections accessible to those who can’t afford to contribute financially.

Focal paper: Urban, M. C. 2024. Climate change extinctions. Science 386:1123–1128. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adp4461

My herpetologist exhusband has been on the couch in agony since the 1960's. He saw it all coming post "Silent Spring". I tried to be his "Little Mary Sunshine" to no avail. He was right, he sounded the alarms, he was famous in the Zoo world for animal breeding. The fact that we are killing ourselves hasn't penetrated here in America.

Sadly, we will surpass the extinction rate of the dinosaurs. From 1960 until 2025 what was remaining on earth at that time has been reduced by anywhere from 75 to 85% worldwide. With the genetic pool shrinking rapidly as well as biodiversity and habitat what is remaining doesn’t stand a chance all caused by humans. How is it that one species can weld that much power. If you take a time machine back 10,000 years ago, this planet was teaming with wildlife. We built cities from one end of the Earth to the other paving over their homes they had nowhere to go but the graveyard 2000 years ago during the gladiator games Rome almost caused the extinction of all the large animals on the African continent out of greed for gory, so don’t expect an optimistic view from me when we still treat animals as an object.