Welcome to the age of nonstationarity

A statistical property that undermines ecosystem management under climate change.

In 1922, commissioners from seven states met to apportion water from the Colorado, the largest river in the southwestern United States.

Based on river flow data available at the time, the commissioners assumed the Colorado would deliver an average water volume of 20.2 billion m3·y-1.

Water allocation policy was then built upon this single estimate.

For a start, their estimate was wrong with respect to 20th century flows because their data came from an unusually wet period of record.

Even worse is the fact that Colorado River flows have decreased a further 19% during the 21st century due to declining precipitation and warming air temperatures.

This mismatch between policy and the reality of the river has led to litigation among states, inefficient water management, and uncertainty over the future of agriculture and development in the region.

The primary mistake of the commission was not in getting the estimate wrong, however. It was in assuming that river flows conform to some long-term average over time — the assumption of stationarity.

Much of the world’s river management policy still clings to the idea that the climate, and thus river flows, will continue to follow average trends observed in historical data.

It is time to abandon these practices and adopt new management techniques that accommodate nonstationarity and uncertainty.1

But, first let’s explain nonstationarity a bit more.

What is nonstationarity?

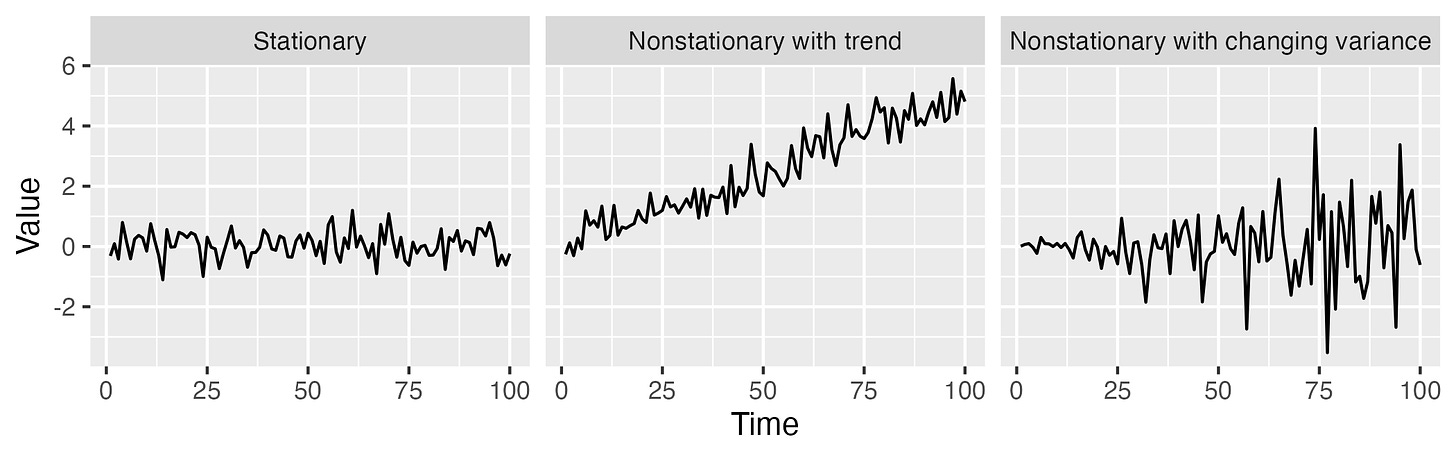

Pretty simple really: stationarity is a statistical property. It means that things aren’t changing through time. Specifically, a stationary time series has statistical properties (e.g., mean and variance) that do not vary in time. By contrast, nonstationarity is the status of a time series whose statistical properties are changing through time. Hopefully the figure I mocked up below demonstrates this concept.

This is the reality of the world we live in. Yet, stationarity, or conditions that fluctuate within a range of variability that persist through time, is fundamental to the way we manage, develop policy and design infrastructure for water resources globally. This stationarity could be over various time-scales including diurnal/daily, seasonal, right through to things like the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. However, stationarity is dead.

“stationarity is dead and should no longer serve as a central, default assumption in water-resource risk assessment and planning”

— Milly et al. (2008)

This is not a problem that is limited to river ecosystems; climate change is impacting ecosystems across the world. All realms are under threat: marine, terrestrial and freshwater. Environmental policies, practices and infrastructure need to be operated in a way that embraces it.

And, although the climate is the poster child for nonstationarity, having been pushed outside of its previously stationary envelope, ecological systems and species responses to their environment can also be nonstationary. Invasive species spread and land-use change are just two examples of massive nonstationary drivers of rapid state change worldwide.

Despite long familiarity with these issues, approaches to managing ecosystems have continued to rely on historical ranges of variability as goalposts for restoration. This is unrealistic. Adopting policies and practises to manage ecosystems under nonstationary dynamics is sorely needed.

So what can we do about nonstationarity?

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, dealing with this level of uncertainty requires long-term thinking. It requires a mindset shift for managers, policymakers, and the public alike.

In reality, my newsletter, as a whole, focuses on this topic. So I can’t cover this in a single post. But I wanted to provide a brief explainer of what nonstationarity is as you may come across this term elsewhere, perhaps in future posts.

Nonetheless, as I mentioned last week in my post focused specifically on river management, we need to: 1. manage for variability; 2. build resilience; 3. anticipate and adapt; and 4. prioritise nature-based solutions, among many other things. Of these, focusing on anticipatory approaches like increasing our capacity to forecast or project the outcome of future events or interventions is critical. However, so too is focusing on adaptive approaches to managing the environment (for more see here); we need to be flexible and learn by doing.

We raised many of these ideas in a paper published a few years ago in Nature. We highlighted that effectively, we can no longer focus solely on restoring to historical conditions because they no longer exist or may no longer exist under future conditions. Instead, we need to be more future focused in our efforts. This is both in the way we focus on restoring ecosystems, but also in our approaches to predicting future ecosystems and in systems for management and policymaking.

Managers and policymakers have tended to either ignore the fact conditions are nonstationary or assume changes are small enough that it is acceptable to continue with stationarity-based design. This simply won’t work as the climate continues to change and we experience more frequent and intense extreme conditions.

Hopefully, this explainer was useful and not too depressing. We know some of the answers, we just need to find ways to get them in the right hands and for those with power to implement them.

Until next time, thanks for reading. Let me know what you think in the comments!

If you’re reading this for the first time, be sure to check out the archives here.

Feel free to click the ❤️ button on this post and considering sharing it to help more people discover it. Tell me what you think in the comments!

If you’re a Substack writer and enjoy Predirections, consider recommending it. It makes a big difference.

Check this out for more on managing rivers:

Much of this early text was written by Dave Lytle as part of an early draft of our Nature paper I cite.

We must become nimble, flexible, and most importantly, very honest. This problem faces us all, and it is frightening, but nothing that can’t be mitigated and adapted to through objective analysis, careful planning, and teamwork. We cannot continue business as usual and still survive, we must change, and that starts by admitting there’s a problem. Our outlook going forward must be non-anthropocentric, where we become agents of positive change, of protection, but ultimately a functional piece of the natural world like we always could have been.

I can only imagine what limited data those men were dealing with when they built the Colorado River allocations. 🙄

What’s more appalling—as you point out so well—is that the management of it has remained the same despite the plethora of new data.

Great article.