To address grand challenges, we need transdisciplinarity, but what actually is it?

A brief guide to the various forms of disciplinarity: intra-, cross-, multi-, inter- and transdisciplinarity.

Last week, I discussed the need to broaden and diversify research in the search for solutions to grand challenges like biodiversity loss and climate change, including the search for win-win biodiversity-climate solutions. One tool in the toolbox is to use explicitly transdisciplinary research approaches. But what actually is transdisciplinarity, and how does it differ from cross-, multi-, and interdisciplinarity? I think much of the time, we don’t actually know.

Transdisciplinarity is a buzzword these days. Research funders, universities and institutes are increasingly wanting transdisciplinary research to create “transformative” impact. The term gets thrown around all over the place, but I’m not convinced those using it always truly mean transdisciplinary. Many times when you hear folks talk about it, they’re often referring to different forms of disciplinarity that differ from explicitly transdisciplinary methods. Unfortunately, this confusion persists into the academic literature and creates barriers to communication1.

So I thought I’d spend a few minutes in this post defining what my understanding of these different forms of disciplinarity are. I will make this brief as there is a lot out there on this topic already, but I do feel it is important to have a clear understanding of how transdisciplinarity, in particular, differs from other forms of disciplinarity. I will talk about this in many of my future newsletters I’m sure, so I hope this guide will help to demystify the term.

Much of my explanation below stems from a seminal paper2 in the early nineties by Marilyn Stember, which outlines a five-step typology of disciplinarity from intra- all the way to transdisciplinarity. While this paper is now over thirty years old, the typology largely persists to this day. The key point: as one moves up this hierarchy, greater integration among discipline occurs.

OK, so let’s briefly run through the various forms of disciplinarity.

Some definitions

Intradisciplinary

This is the traditional approach to research. Work is conducted within the boundaries of a single discipline. For instance, ecologists would collaborate with other ecologists on an ecological problem (intradisciplinary collaboration). Following this approach is the standard way of doing research, and clearly allows for major progress through specialisation, but may miss out on outside perspectives and insights from other disciplines.

Crossdisciplinary

I tend to think of crossdisciplinarity in two ways. Based on the original definition from Stember, one discipline is viewed through the lens of another, but the disciplines remain separate. So, in essence, crossdisciplinarity involves knowledge exchange between disciplines, where knowledge from one discipline enriches another without integration. To demonstrate this, Stember uses the example of a physics professor describing the physics of music. So one discipline is helping to inform another.

To confuse matters, crossdisciplinarity can also be used as a general term referring to any activity that crosses academic disciplines. I tend to think of it either way. In this context, crossdisciplinarity can refer to anything from multidisciplinary, where disciplinary insights are kept separate, through to fully integrated transdisciplinary melting pots.

Multidisciplinary

Multidisciplinarity, involves examining an issue from the perspective of multiple disciplines at once. No integration is sought among the disciplines. Instead, each discipline focuses on the problem within their own disciplinary boundaries in parallel. That is, knowledge gained from each discipline remains within the discipline and is placed alongside the findings of other disciplines in the same research project.

Multidisciplinary approaches can result in really clear insights within disciplines and help to tackle problems from multiple fronts, but can lack cohesive answers. Multidisciplinary collaboration is one of the most common approaches to collaboration across disciplines. This might be as simple as an ecologist, geomorphologist and hydrologist working together on a joint river management project such as designing a new dam operation programme. They would provide their own disciplinary expertise and analysis in parallel with limited collaboration. There will be separate ecological geomorphological, and hydrological results or recommendations.

Interdisciplinary

Interdisciplinarity involves a higher level of cooperation. It integrates knowledge, concepts, methods and theories from across disciplinary boundaries to tackle complex problems. Here, disciplines are interconnected. This involves true synthesis of ideas across disciplines where interdependent bits of knowledge are melded together into harmonious relationships. Working towards a common goal or problem enables new knowledge to emerge that can’t necessarily be broken down into its disciplinary ingredients.

The key part to me is that interdisciplinary research is used to tackle problems that are often so complex that they can’t be answered satisfactorily by any one discipline, or are beyond the scope of a single discipline. Disciplines have to be integrated to find solutions to those problems. This differs to multidisciplinarity, where the individual disciplines continue to work in parallel finding their own solutions to different parts of the problem.

Here, disciplinary boundaries are crossed and integrated. This results in new perspectives in response to a common problem. Being problem oriented is key here.

Using the dam example above, the ecologist, geomorphologist and hydrologist would work more closely, first trying to understand the river ecosystem holistically, including the interconnectedness of biophysical processes. Then, rather than working independently, they would integrate their analyses to understand how dam operations would impact the joint hydrological, geomorphological and ecological processes.

Transdisciplinary

The top of the hierarchy. This is where research gets very tricky. Rarely is truly transdisciplinary research performed. It encourages thinking outside the box and innovative approaches to collaboration. But it requires a set of explicit methods to enable it to happen. Transdiciplinarity doesn’t emerge by simply joining forces with a diverse group of people. Instead, it requires trained professionals who know how to facilitate the process (but I won’t go into those details here).

Transdisciplinarity transcends disciplinary boundaries entirely. It aims to find holistic solutions to complex problems via creating unified conceptual and intellectual frameworks that don’t belong to particular disciplines. The key point again here is the focus on real-world problems — it is a problem-first approach.

One important point here is that transdisciplinarity integrates diverse knowledge systems beyond academic disciplines, including indigenous knowledge and insights from stakeholders, such as policymakers and community members. Indeed, some argue that research cannot be transdisciplinary if the participants are all academics. Instead, transdisciplinarity needs to be a reflexive process between academics and non-academics.

The goal is to co-create knowledge for addressing grand societal challenges in an inclusive manner. So, at this point, you can no longer see the ingredients of research or the traces of disciplines that led to the outcome. Instead a new property emerges that didn’t necessarily exist before the work began.

Again, using the dam example, these academics or researchers would join forces with non-academic partners to co-develop the research from the outset and collaborate throughout the process. Stakeholder engagement is key here. It could include the dam operators, members of the community, policymakers and so on. The approach would be solution-oriented, actionable, and iterative. Transdisciplinary collaboration involves ongoing dialogue, reflexivity, and adaptation to evolving circumstances, ultimately leading to the implementation of the revised dam operation programme.

Summary

In summary, the key distinctions are:

Intradisciplinarity: working within a single discipline.

Crossdisciplinarity: viewing one discipline through the lens of another, but disciplines remain separate. Alternatively, a general term referring to any activity that crosses academic disciplines.

Multidisciplinarity: multiple disciplines working in parallel on a single problem without integration.

Interdisciplinarity: multiple disciplines working together, integrating knowledge, to address complex problems.

Transdisciplinarity: transcends disciplinary boundaries to create a unified framework addressing complex issues; involves collaboration beyond academia.

So, as we move up the hierarchy, we increase the level of integration, exchange, or transcendence of disciplinary boundaries. By doing so, we open new doors, perspectives and insights for solving complex problems. Issues at the climate-biodiversity-water nexus are often the sort of wicked problems we need to tackle with increasingly integrated methods.

I hope you found this helpful. Remember to click the ❤️ button on this post if you enjoyed it and share it around. Tell me what you think in the comments! I’d love to hear your thoughts.

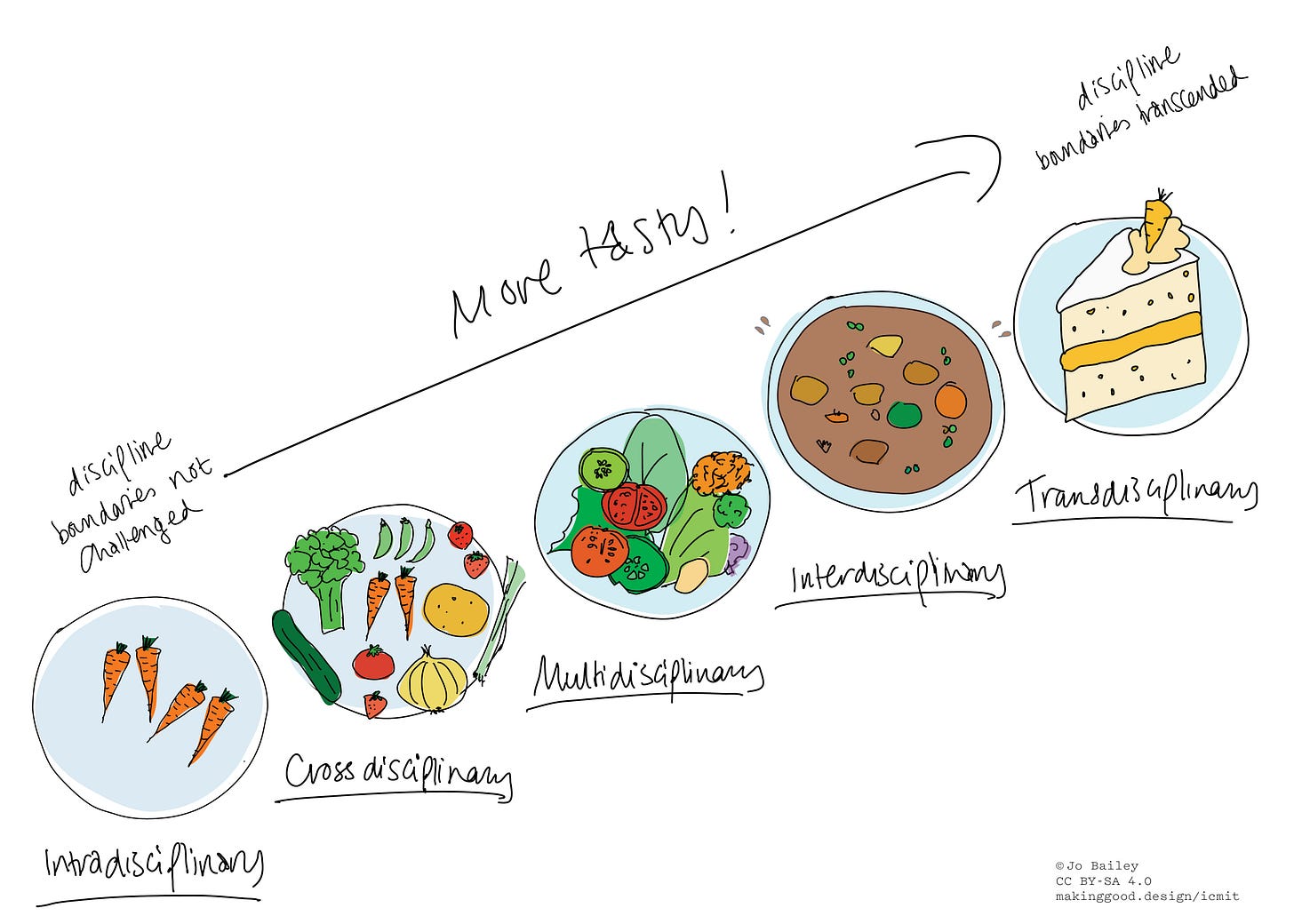

I’ll leave you with this awesome image created by Jo Bailey, a fellow member of Te Pūnaha Matatini, the New Zealand Centre of Research Excellence in Complex Systems. This helps to visualise the hierarchy of disciplinarity I’ve discussed above, using recipes as a metaphor.

Mauser, W., G. Klepper, M. Rice, B. S. Schmalzbauer, H. Hackmann, R. Leemans, and H. Moore. 2013. Transdisciplinary global change research: the co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 5:420–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.001

Tress, G., B. Tress, and G. Fry. 2005. Clarifying integrative research concepts in landscape ecology. Landscape Ecology 20:479–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-004-3290-4

Stember, M. 1991. Advancing the social sciences through the interdisciplinary enterprise. The Social Science Journal 28:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0362-3319(91)90040-B

This was a very interesting article and reminding me of a book I borrowed off you called, Consilience The Unity of Knowledge written by Edward O. Wilson in 1998. He talked about the linking together of different disciplines to form strong conclusions and I think he was on the money. Your article explained disciplinarity in a way that non academic people can relate to and understand. We need a wide variety of people tackling the world's big problems but we also need more academic people like yourself explaining the complicated stuff to the general public and getting those important messages out there. The artwork was great too!

But academic disciplines are themselves artificial constructions - and partly a consequence of the organisation and financing of Universities, right? So disciplines, are responding to a mixture of institutional managment needs and imperatives (like lab space and dedicated infrastructure) as well as constantly changing research frameworks. The main point is that if you are working on these complex problems outside of an academic context (the case for more and more scientists), all these definitions amount to a rather rigid, artificial view of interactions between individuals working on a question.

I've been on both sides (academic, non-academic) and I think these disciplinarity concepts get in the way of the research by adding extra labels which ultimately only reinforce and benefit those persons inside Universities. There is nothing about them that ensures new ideas will be worked out, or that solutions will be found. Academic research institutions in their organisation and with their rules of function, including self-evaluating their own research, continue to strenthen disciplinary barriers. When they launch initiatives about "X-disciplinarity" it mostly amounts to saying officially "yes, you can go in another building" :)

On the other hand, underlying the rise of all the "X"-disciplinarity concepts is the dematerialisation of large swaths of scientific work. This has meant that individuals from different "disciplines" formerly separated by their tools (and institutions), are now using very similar methods (e.g. network analysis, Bayesian reasoning, image analyses, ...). For example, when humanities became the "digital humanities", as a theoretical ecologist I can share data and analyse problems with historians, archeologists, anthropologists and economists etc. all using very similar mathematical and statistical tools. This means research frameworks of concepts are merging too. IMO, the disciplinary divides that remain are slowly being transformed into "those who need access to instruments and objects" (materials analysis) and "those who do not".

Ultimately, IME, the research progress depends on the specific skill sets and compatibility of the individuals involved in a group, along with a dose of good will and some luck. :)