The surprising similarity between rivers and trees

Rethinking rivers mini series, Post 1 of 3: Rivers are much more than channels of flowing water, they're networks.

It's been World Water Week this week. It may be wrapping up, but the conversations it sparked are just beginning — and they matter more than ever. Over the next few days, I’ll be sharing a three-part series on some unique aspects of rivers and why they’re so challenging to manage. We’ll explore how rivers function as networks, their unique rhythms, and what that means for conservation and restoration. Don't worry, these won't be long-form deep dives. Just short, sharp pieces to keep you engaged and thinking.

Freshwater needs all the help it can get. By sharing these posts, you’re helping raise the visibility of ecosystems that are often overlooked — and increasingly at risk. Let’s get more people thinking about rivers not just as scenery, but as living systems worth protecting.

When most people think about a river, they picture a channel that carries water out to sea. Often, people fear rivers because of their destructive force. If you're lucky some people value them for the food they provide. But far too many rivers are undervalued.

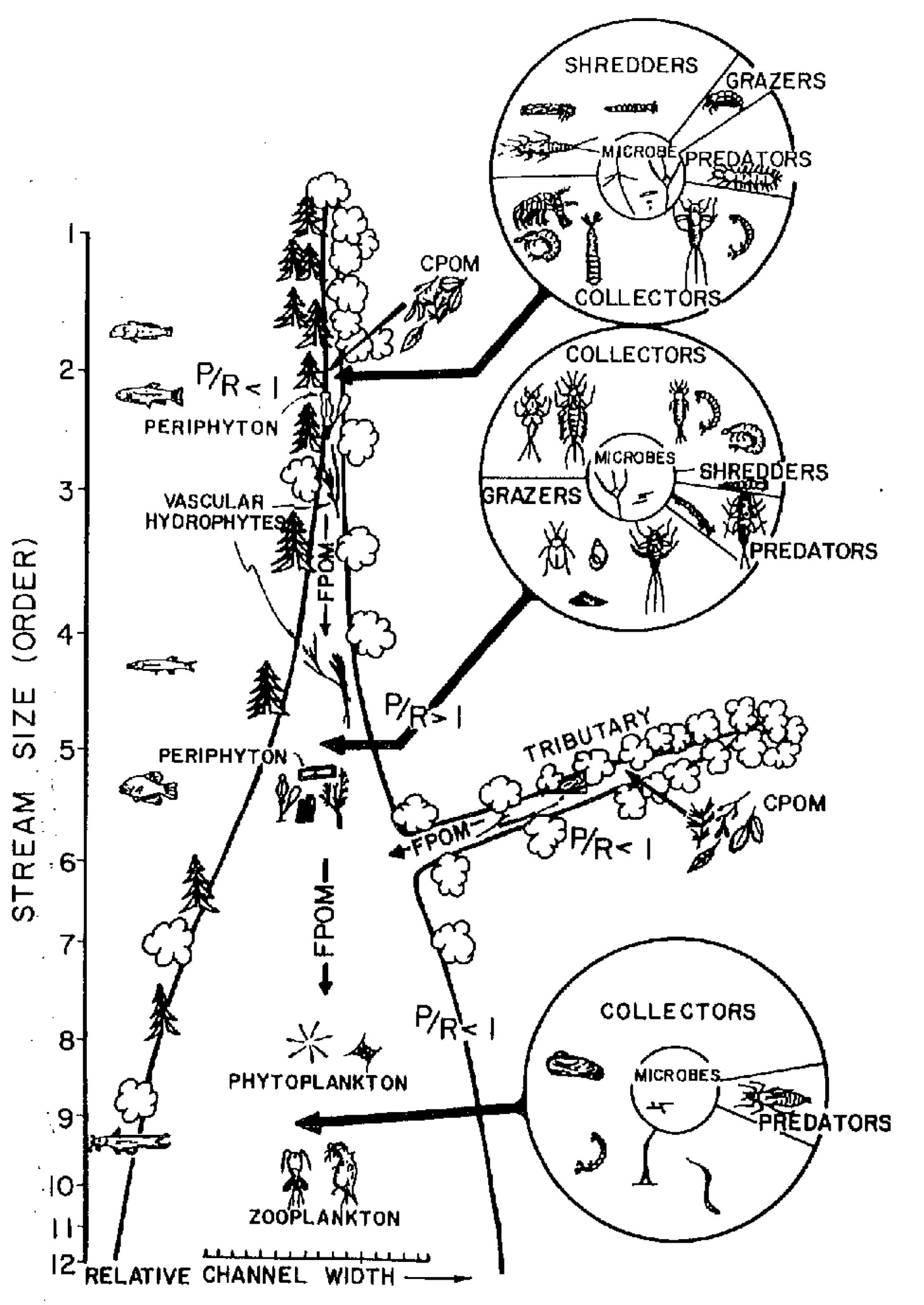

Even river ecologists historically thought of rivers as linear systems that change from the headwaters to the sea. To be fair, they are and they do. But this view overlooks one key element. Something that shapes how biodiversity — the bugs, the fish, the microbes, the birds — is organised in rivers:

Rivers are networks.

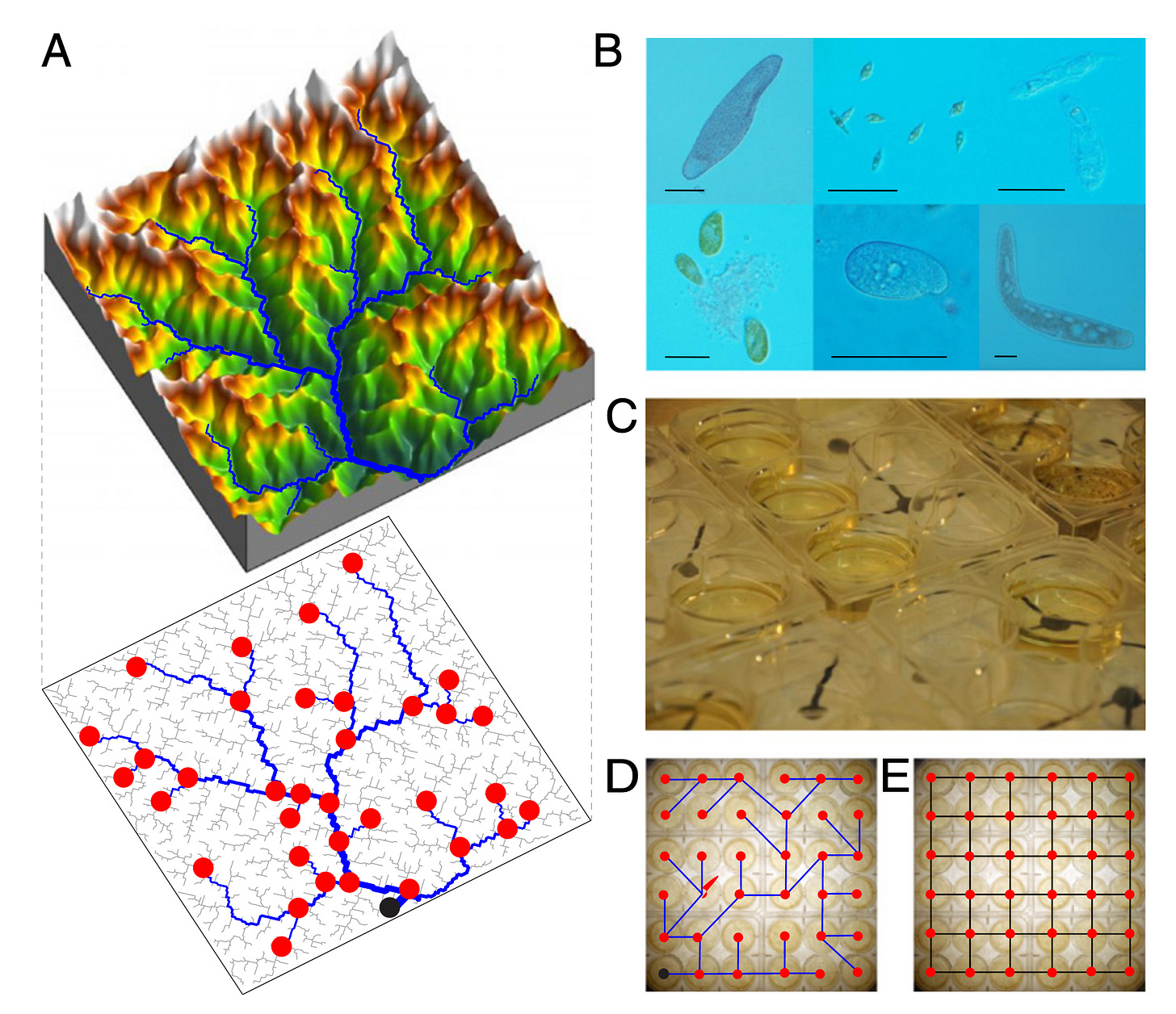

More specifically, they're hierarchical dendritic networks. Who the what now? Let's try that again. They're organised like trees (dendritic) that go from small headwaters and branch into large mainstems in a way that's highly connected.

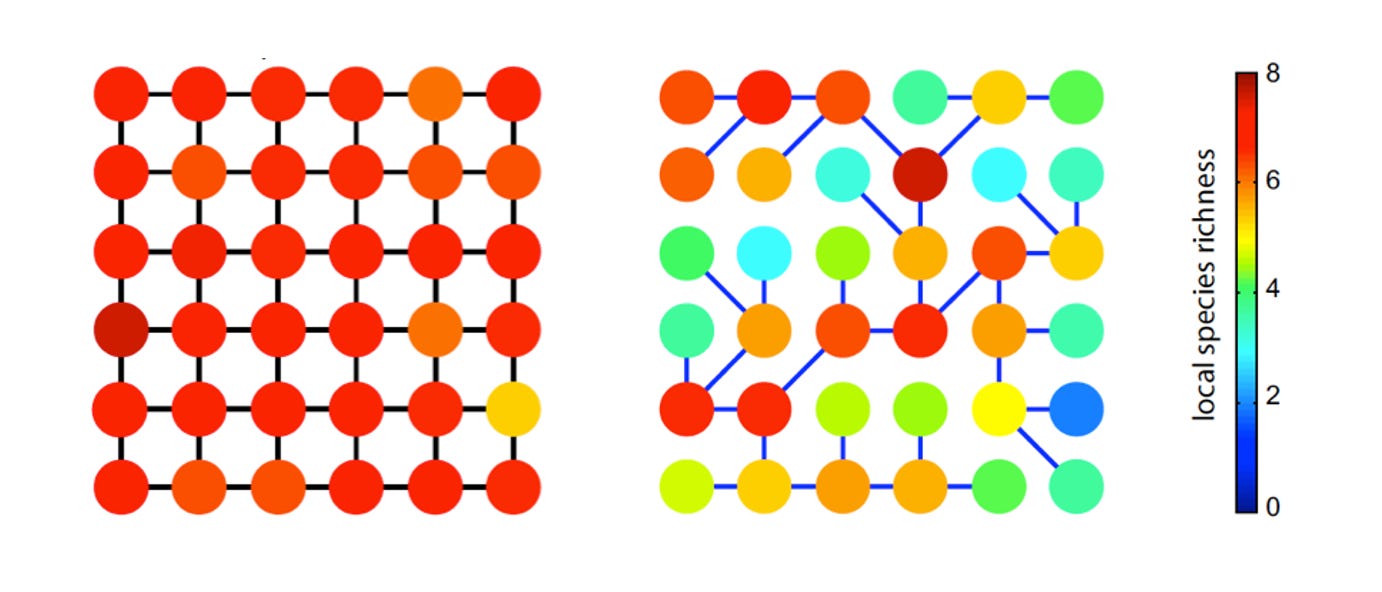

What's very cool here is how biodiversity is organised. The obvious assumption would be that there's more diversity in larger downstream habitats. And that's correct — if you're thinking solely about how many species are at a particular location. But if you zoom out and ask where biodiversity sits more generally across whole river networks, it might just be the opposite. Sure, each of those tiny little branches might host fewer species, but they're different from each other. Add all that branch-to-branch variation up, and you get a lot more diversity1.

And it's not just because the conditions in each of these small headwaters differ — they might actually be the same. But it's also that species can't necessarily get to each of them. So differences in dispersal rates of species mean some species can get to some headwaters and not others, leading to variation in who gets where. As a result, you get greater biodiversity among all the different branches. This is less so for downstream habitats. So they tend to be more homogeneous.

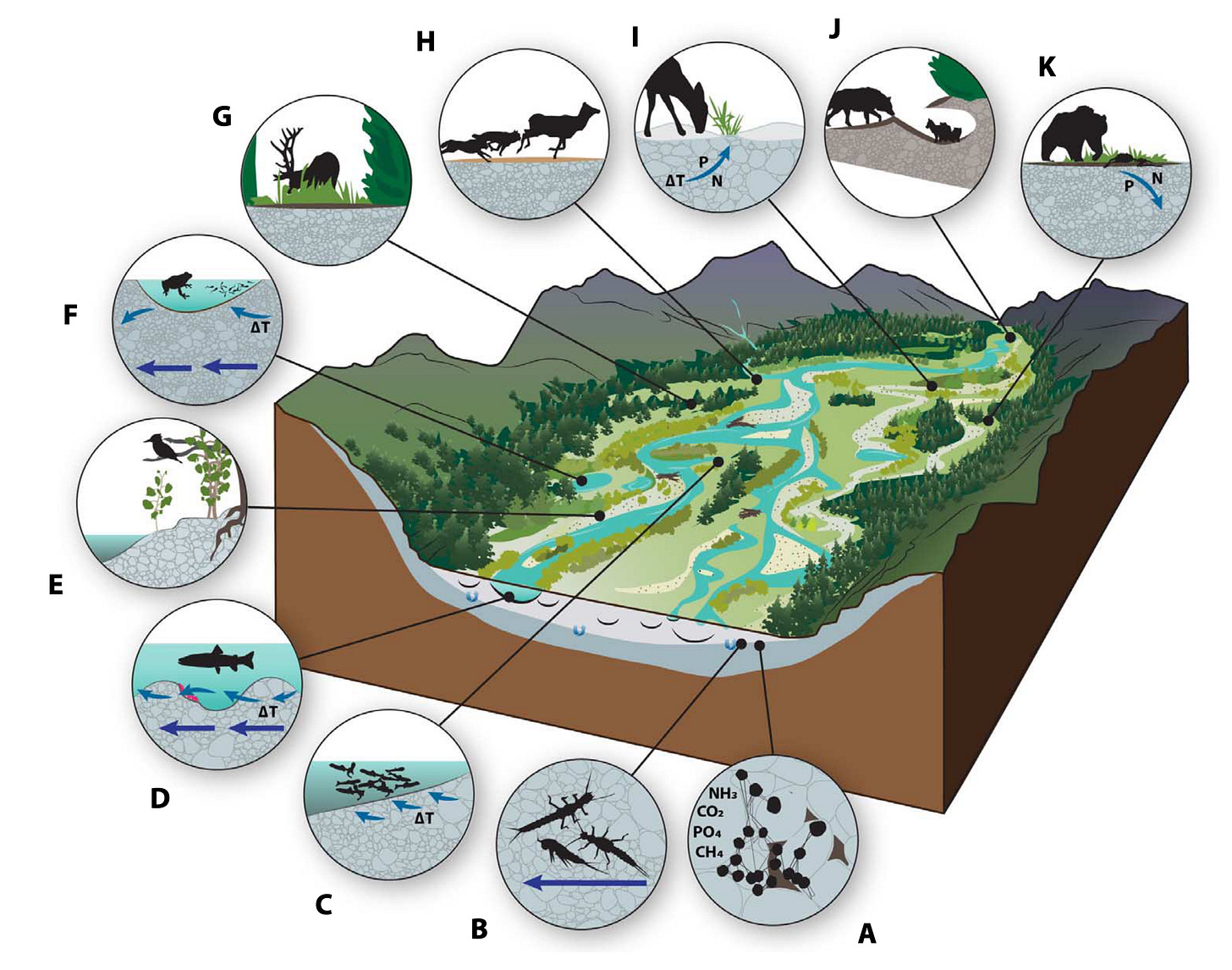

So yes, rivers are connected longitudinally — along their length — and form into networks.

But they're also connected laterally to their margins — if they are functioning naturally. Floods pulse into their floodplains, replenishing soils (there’s a reason we farm on floodplains!), allowing fish to forage on the rich terrestrial life, transporting seeds of riparian trees into their floodplains. These flood pulses are fundamental to many tropical rivers because they're so predictable. And when rhythms are predictable, life evolves to sync with them.

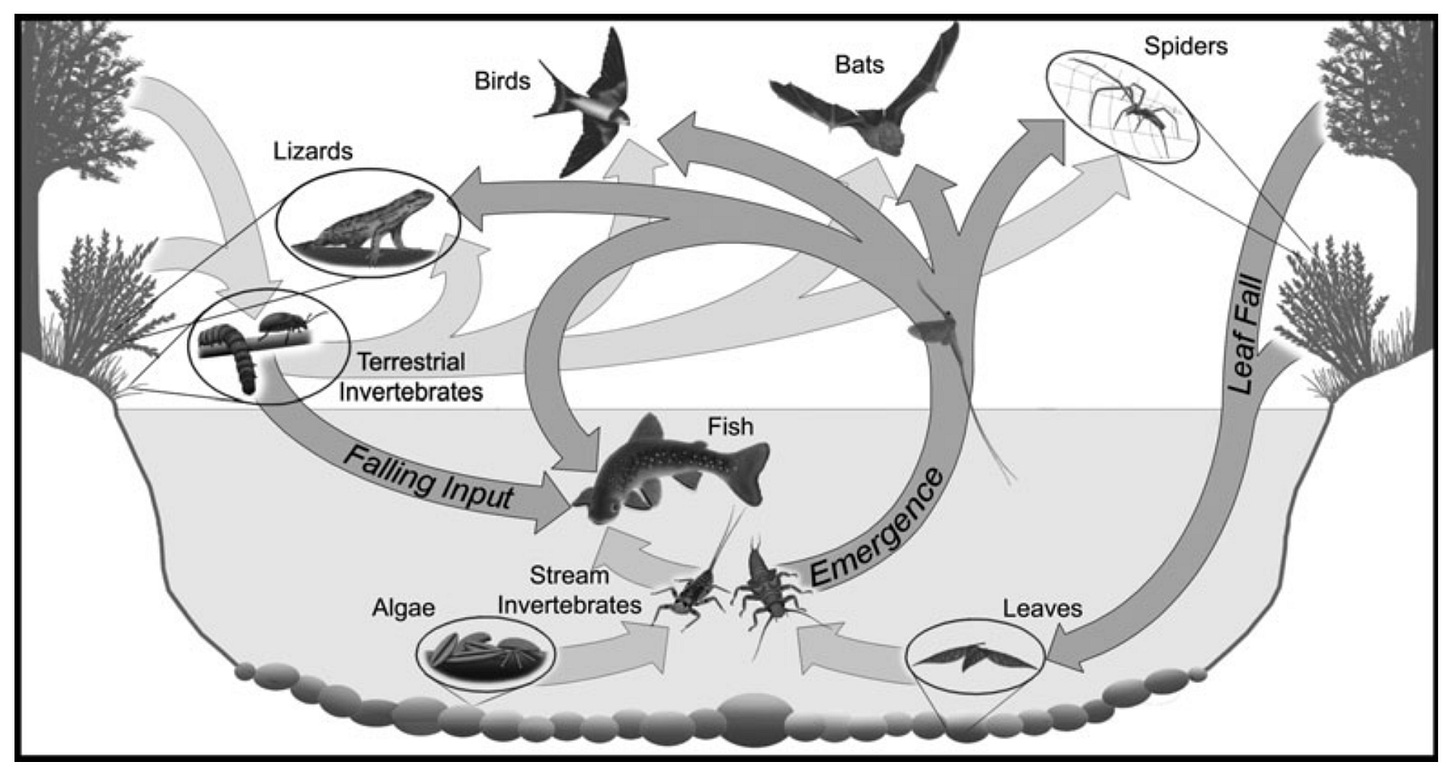

And this lateral connectivity isn't all one-way — it's reciprocal. Aquatic insects emerge from rivers and feed riparian bats, birds, and beetles. In reverse, terrestrial insects fall into the water, feeding fish. Leaves drop, fuelling microbes and shredding insects. Energy flows out onto the land, and then flows back in. These exchanges form the basis of food webs that connect the land with water. They're seasonal, essential, and fascinating.

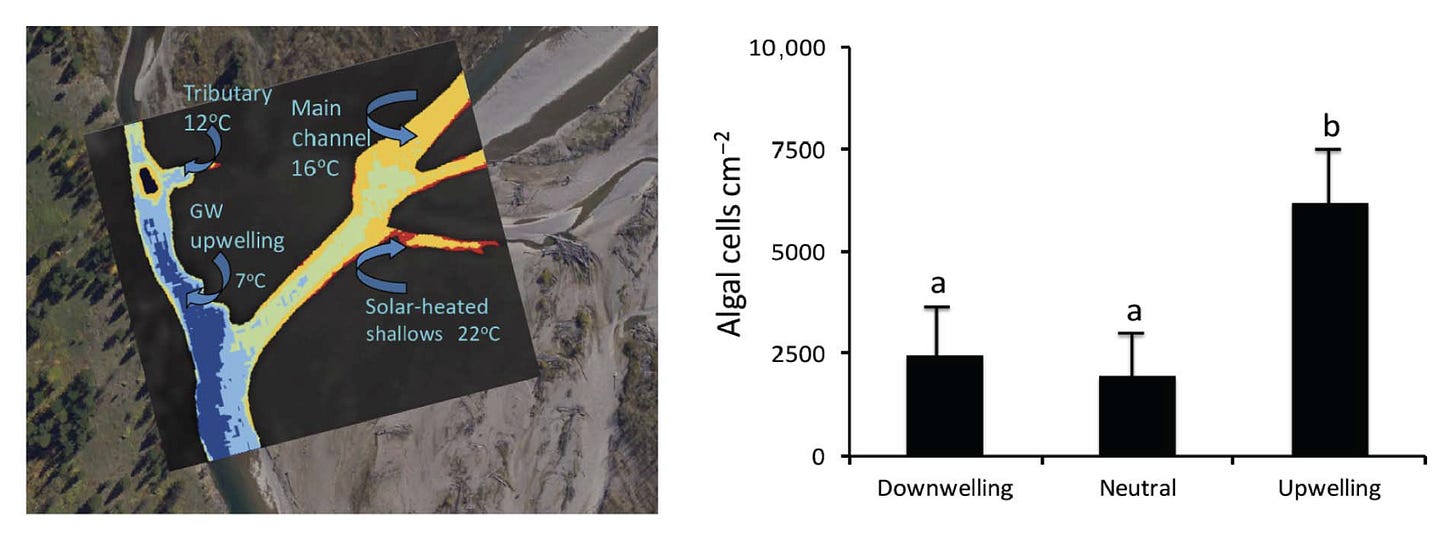

And let’s not forget vertical connectivity. Water upwells from below, bringing nutrients and cooler temperatures. Groundwater and surface water interact in ways that shape habitat quality, thermal regimes, and ecological processes. And specialist life occupies these places, whether in the springs that provide respite from temperature extremes, or species occupying the deep, dark places several metres under the surface.

Rivers are not just water flowing to the sea — they’re living networks that connect land, air, and underground worlds. But they have been and continue to be fragmented, channelised, and stripped of their connections — often in the name of progress. When we break those connections, we don’t just lose species. We lose resilience. We lose the ability of rivers to recover, adapt, and support life. And we continue to do it at pace. So let’s share the love for healthy, functioning rivers! And let's keep these connections for the sake of the life they support.

Coming up in the next post

Rivers aren’t just connected in three dimensions. Stay tuned for the next post that talks about the fourth dimension, time!

If this post resonated, consider subscribing to follow the rest of the series.

And biodiversity is fundamental for a variety of reasons:

Am thinking this speaks to the profound truth that everything in our world is interconnected, and the health of one part directly impacts the whole. The idea of rivers as living networks, rather than just channels for water, is a perfect metaphor for the intricate web of life on Earth.

While out on many river's in my lifetime, it's not lost on me that the flow connects mountain streams to sprawling deltas, nourishing the land and all its inhabitants along the way, our own lives are part of a continuous cycle of connection.

I like to think when we mistakenly see a river as a singular, isolated entity, we fail to recognize the myriad of relationships that define its existence. Remembering the insects that feed the fish, the birds that nest in the trees on its banks, the groundwater that sustains it even in drought. It's now more than ever important to teach the concepts of the circle of life in its truest form: an endless loop of give and take.

I hate that when we disrupt this cycle by damming, dredging, or polluting rivers, we do more than just alter their physical course. We failed with our Corps of Engineers in our human efforts break what is natural to suit our own need to conquer and harness bodies of water.

We certainly didn't understand the consequences when we severed the links between species and ecosystems, leading to a loss of resilience and an inability for the system to recover.

Similarly, when we fail to nurture our own connections to the world around us—to other people, to animals, to the natural environment—we weaken our own collective strength. We lose the ability to adapt and thrive together.

Your call to "share the love for healthy, functioning rivers" is therefore not just about conservation; it's an invitation to acknowledge our place within this grand, interconnected network. By working to restore and protect these living arteries of our planet, we are also nurturing our own connections to all creatures.

I find your in-depth explanations refreshing and a very worthwhile. Looking forward to your next post on this important topic.

River networks in the framework of complex network theory