The many faces of invasive species impacts

A quiet forest, a loud debate, and the science that makes sense of the widespread and diverse impacts of invasive species

As I walk along the forest trail, I'm surrounded by stillness. I hear the sound of my own breath and the regular rhythm of my footsteps on the soft earth beneath. But not much else.

I'm in a forest deep in the backcountry of Aotearoa New Zealand. It's a meditative experience.

But, while this serenity may be good for my soul, it’s not all good news. In fact, it's not good news at all. Shouldn't I be hearing the songs of our unique endemic birds?

Yes, under normal circumstances, they should be bombarding me with their cacophony of chirps, trills, warbles, hoots, and shrieks. But here, the predator control programme isn't keeping up. Stoats, ferrets, weasels, possums, cats, rats, and mice are annihilating the local populations of birds. This is all too familiar in NZ. Our endemic fauna evolved in the absence of any mammalian predators. So they're defenceless to non-native predators. But since the arrival of humans, these predators have run rampant, decimating birds, lizards, plants, and insects across the country.

And while that silence hits me personally, it also reflects a bigger scientific gap: we haven’t had a clear framework to make sense of the many, often cascading, ways that invasive species cause harm.

NZ is not alone here. It's a story that's all too common around the world. To make matters worse, predation isn't the only problem – far from it in fact. Wouldn't it be simpler if it were! Instead, invasive species bring a whole complex suite of issues ranging from increasing fire risk to disease spread.

Yet, I've seen my fair share of content, particularly here on Substack, suggesting invasive species aren't a problem, including saying our default assumption should be that invasive species are harmless to beneficial!

I'm happy for debates to be had in the open. This is how it should be. But I'm also keen to make sure the record gets set straight, particularly on topics like this, where so much potential harm can be caused. The fact of the matter is invasive species are one of the five main drivers of global biodiversity loss. Simple as that. But in reality, they're doing much more than driving species to extinction, they're affecting our livelihoods too.

So I'm here to try to put the record straight. I'll do so while describing our recent paper1 that introduces a new typology of the multitudinous impacts that invasive species bring.

But bear with me. First, let's get some terminology straight.

Not all non-native species are invasive

Yes, not all non-native species are invasive. Far from it, which is I think where a lot of issues arise. The term invasive can get overused at times. It's important to differentiate species that are non-native but not problematic from those that are problematic. In particular, those that spread beyond where they are introduced.

But consistent terminology is no easy task in such a heated and nuanced space. A recent paper highlighted 37 previous efforts that have attempted to provide clarity on the terminology used in invasion biology! The paper, by a large list of invasion biology experts, sought to clarify these terminological issues. They proposed the following distinctions

"(i) ‘non-native’, denoting species transported beyond their natural biogeographic range, (ii) ‘established non-native’, i.e. those non-native species that have established self-sustaining populations in their new location(s) in the wild, and (iii) ‘invasive non-native’ – populations of established non-native species that have recently spread or are spreading rapidly in their invaded range actively or passively with or without human mediation."

In our paper that I introduce below, we define invasive species as "a non-native species that is transported beyond its natural biogeographic range. When it establishes and spreads (i.e., stages of the invasion process) it is usually referred to as an invasive species." Note, this and the above definition refrain from mentioning impacts, but these are implicit because to spread, a species has to displace or disrupt something else.

For the rest of this post, I'll stick with the term invasive to represent those that actively spread beyond their non-native range.

Now that we’ve cleared up the non-native vs. invasive terminology, let’s move onto our typology, which serves a different purpose: offering a structured classification of impact types to understand the diverse and often cascading ecological impacts of invasive species.

The diverse impacts of invasive species

We've already established that it's not just the effects of invasive species on native species that's the problem — it's all the other impacts that we often overlook, like changing soil chemistry or altering primary production. Not only are the ecological impacts of invasions numerous and diverse, we also mix up things like causes and consequences. It’s a messy space. What to do, then?

Well, this is a problem we're trying to fix. Led by Laís Carneiro and organised by Franck Courchamp, we created a structured typology of these impacts. In hindsight, it looks simple, but it’s anything but that. A lot went into this piece of work. And I’d argue that it’s a really important piece of work (as an author, I may be biased though).

So, the key task here was to identify and create a typology (a classification or categorisation of sorts) of impact types that can be used in characterising, quantifying and understanding the impacts of invasive species – more than just, say, an impact on the size of a native species population. Such a structured way of characterising impacts has been missing so far and is needed to help drive the field forward.

The first stage in doing so was running a Delphi process. If you recall from my post on horizon scanning a few months ago, a Delphi process is an iterative, anonymous participatory method that is used to gather and evaluate expert knowledge. Specifically, complex problems are tackled collectively via a structured communication process where experts anonymously weigh in across several rounds. This process helps build consensus without the problem of groupthink as I alluded to previously. It’s especially useful for complex, uncertain topics like this. During this process, a list of proposed impact types was presented to 60 leading experts in the field and two rounds of voting followed.

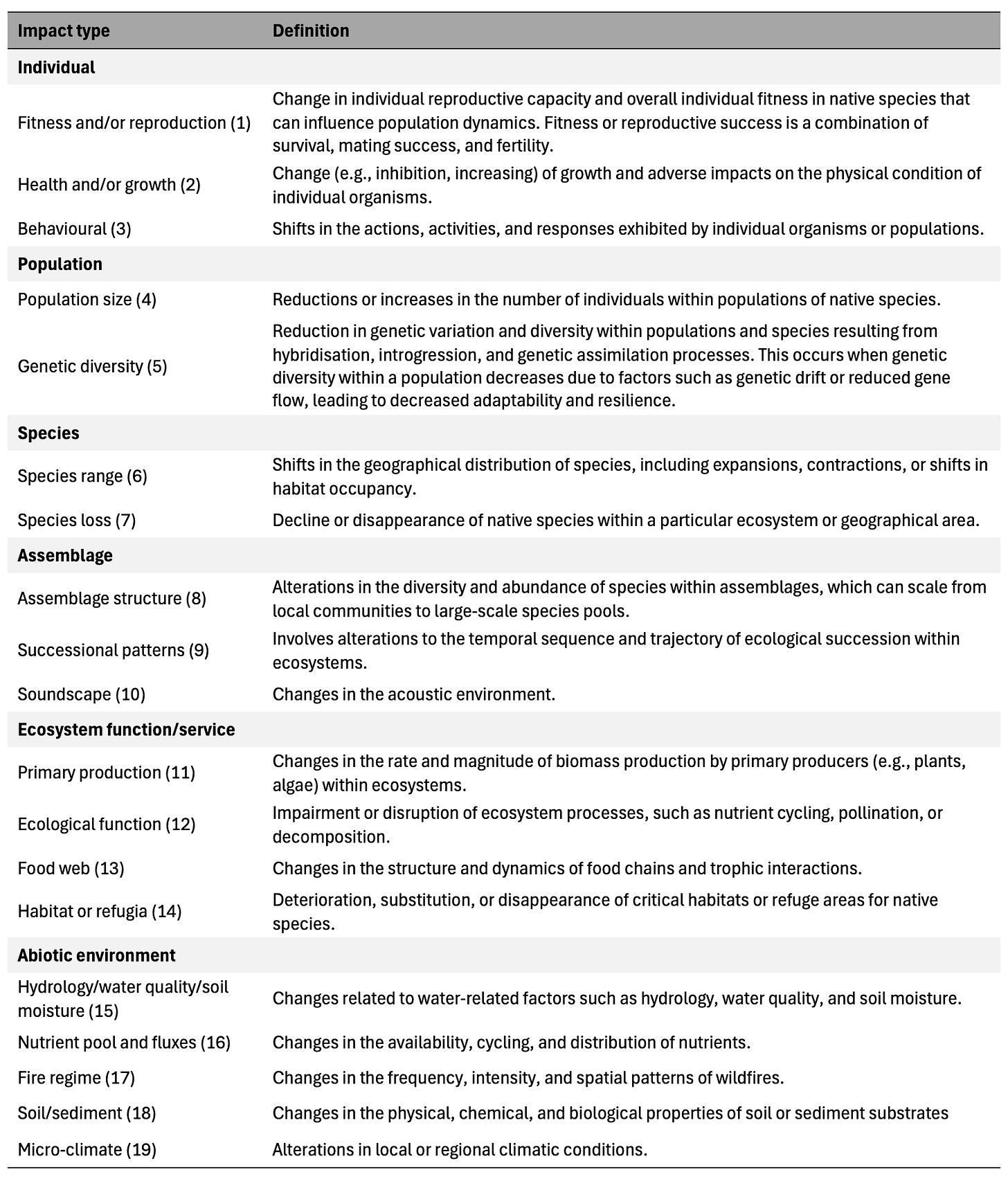

The result? Nineteen distinct impact types across six levels of ecological organisation: (i) individual/organism, (ii) population, (iii) species, (iv) assemblage, (v) ecosystem, and (vi) abiotic environment.

The range of impacts types and on what level of ecological organisation they sit can be found in the figure above. Below, I provide definitions of each of these impacts, taken from the table in the paper.

As you can see, invasive species impacts are diverse, complex, and widespread, beyond their direct impacts on native species. We often focus on their individual- or population-level impacts, but they can change food webs, erode genetic diversity (which makes species more vulnerable to ongoing threats like climate change), alter how ecosystems evolve through time, change soundscapes, change how ecosystems function (e.g. process nutrients, store carbon etc.), and even modify the physical structure of the environment, such as through altered hydrology, fire regimes or even microclimatic conditions.

It's a diverse, complex soup of impacts. If we focus on the few most obvious things, we miss the big picture of how intense invasive species impacts can be.

Impact cascades

Of course, while each of the 19 impact types operate primarily at one of these six levels, they can cascade to affect other levels and impact types. For instance, the loss of a native species from disease can have multiple cascading impacts, such as altering the structure of food webs.

"Such changes can disrupt the trophic interactions and energy flow within the ecosystem, potentially shifting ecosystem functions or services. For example, when native amphibian populations began disappearing in Central America after the introduction of chytrid fungi, the resulting loss of predation on mosquito larvae and adults caused an explosion of mosquito populations; this in turn increased the incidence of pathogenic insect-borne diseases such as malaria in humans living nearby"

A couple more examples of the direct and indirect effects of invasive species across levels of organisation and types of impacts are provided in the figure below.

Looking for positives

Let's get one thing straight. We shouldn't be demonising non-native species, or invasive species for that matter. It’s not their fault. In NZ, we have a pretty unhealthy relationship with invasive species — they’re like an enemy of the state given the widespread effects they have on our forest ecosystems. Demonising them doesn’t help. But that doesn’t mean we should just let them loose to do their thing — the consequences of which are dire.

It's also important to be aware that there can be benefits to be gained from non-native species (note the ‘non-native’, not ‘invasive’ terminology here as it’s rare that an invasive species should be accepted without efforts to eradicate it) among their negative impacts. A recent paper did a nice job of highlighting this. But, again, just to make it abundantly clear, there is a difference between simply a non-native species and an invasive non-native species. Think about the vegetables in your garden: they're most likely non-native. But they don't spread elsewhere, thus they're not invasive. For invasives, the costs outweigh the benefits, simple as that.

Where to from here?

Invasive species are a major threat to biodiversity worldwide, there’s no doubting this. And it's not just biodiversity at risk. Their impacts are costing us! Did you know species invasions have collectively cost a minimum of US$1.288 trillion over the last few decades (1970–2017).

Thankfully, plenty of folks are doing a lot to improve our understanding of their impacts and what to do about them. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) Thematic Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and Their Control recently reviewed more than 13,000 scientific publications and reports in 15 languages as well as Indigenous and local knowledge on all taxa, ecosystems and regions across the globe (resulting in a 1000 page report). Thankfully, there is a summary for policymakers and a recent summary of summaries.

The result? A clear indication that there is a “major and growing threat of invasive alien species” but there are “ambitious but realistic approaches to manage biological invasions” that must be put in place now.

Their highlights:

“Interactions among drivers of biodiversity loss are amplifying biological invasions”

“Prevention is the best option for managing biological invasions”

“Other tools are available when prevention is not possible”

“Management benefits from engagement with stakeholders, Indigenous Peoples and local communities”

“Information sharing is needed across borders and within countries”

“Need for commitment to comprehensive and truly global information systems”

“Aspirational and ambitious goals can be achieved”

Beyond those grand goals, I hope this post has helped you realise that invasive species impacts are indeed problematic (if you’re one of the few that didn't already think so), and that their impacts are more diverse than is commonly conveyed.

Our typology isn’t just academic. Yes, from an academic standpoint, I’m hopeful our paper will be useful for downstream synthesis efforts, helping to improve the way we measure, categorise and quantify ecological impacts globally. But more importantly, policymakers, practitioners, conservationists will be able to better understand impacts, guide risk assessments, and prioritise interventions. Here’s to progress!

Let me know what you think in the comments. I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Carneiro, L., B. Leroy, C. Capinha, C. J. A. Bradshaw, S. Bertolino, J. A. Catford, M. Camacho-Cervantes, J. Bojko, G. Klippel, S. Kumschick, D. Pincheira-Donoso, J. D. Tonkin, B. D. Fath, J. South, E. Manfrini, T. Dallas, and F. Courchamp. 2025. Typology of the ecological impacts of biological invasions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 40:563–574.

For the general public they may not see the ramifications of invasive species. For example, I work in the middle of a wildlife refuge. Folks come there and see the osprey, pelicans, seagulls, and an abundance of flowers. The impression they may get is that all is fine in this corner of Southern California.

Yet the island is completely overrun by invasive ants from Argentina. In the ten years that I've been there, I've never seen a native ant. Recent science confirms that the Argentine ants push out the native ants. When I go to the mountains, the landscape can be abuzz with native carpenter, sweat, and mason bees, bumblebees too! Although I see these creatures from time to time at my worksite, it's mostly populated by European honeybees.

About half of the flowers folks see at the refuge are invasive iceplant from South Africa and daisies from Europe. If we didn't push them back, they would take over the island.

In the meantime, native plants and animals are evolving to adapt to the presence of the invasives. The Argentine ants spread parasites and disease for almost all the native plants, placing evolutionary pressure on them.

And people just get used to invasive species and think of them as natural. The vistas of California, with the tan hillsides is said to be iconic, views seen in thousands of Hollywood movies. Those tan hillsides are covered with invasive European grasses.

I will never get all the Japanese honeysuckle and Russian privet removed from our woods but that doesnt stop me from trying. The reward of seeing a redbud tree that had previously been obscured or an orchid peeking up through the leaf litter is all the reward I need. Every little but counts.