The wealthy contribute disproportionately to planetary decline

But they can also have the greatest role in turning things around

Life just isn't fair sometimes.

That may sound like sour grapes, but it's true. Frustratingly, much of the world bears the brunt of consequences driven by the actions of a privileged few.

Did residents of Kiribati benefit from the excessive burning of fossil fuels or forest clearance by wealthy countries, or the overconsumption of goods and services by the wealthiest individuals? Certainly not. Yet, their very existence as an island nation is increasingly threatened by sea-level rise caused by human-induced climate change. As are many other low-lying nations around the world.

A recent study has identified just how unbalanced the contributions of the world's wealthiest people are to crossing planetary boundaries.

But first, a little recap on the planetary boundaries framework and a reminder that we have already crossed six of the nine as of last year.

Six of nine planetary boundaries have been crossed

The planetary boundaries framework uses Earth system science to understand the key processes that maintain the stability and resilience of Earth as a whole. It identifies how much human pressure each of nine key processes can take before the Earth leaves a "Holocene-like" state, which has enabled humans to thrive for thousands of years. This state, characterised by relatively stable and warm conditions, is what allowed agriculture and modern civilisations to evolve.

Last year, a paper came out highlighting that six of the nine planetary boundaries have been crossed. This means for each of these boundaries—biogeochemical flows (phosphorus and nitrogen cycles), freshwater change, land system change, biosphere integrity, climate change, and novel entities—that the Earth is beyond the safe operating space for humanity. Of the remaining three—ocean acidification, atmospheric aerosol loading, and stratospheric ozone depletion—ocean acidification is dangerously close to transgressing its boundary too.

Key among the reasons behind these changes are the usual chorus of excessive consumption of goods and services, unsustainable production, and resource extraction.

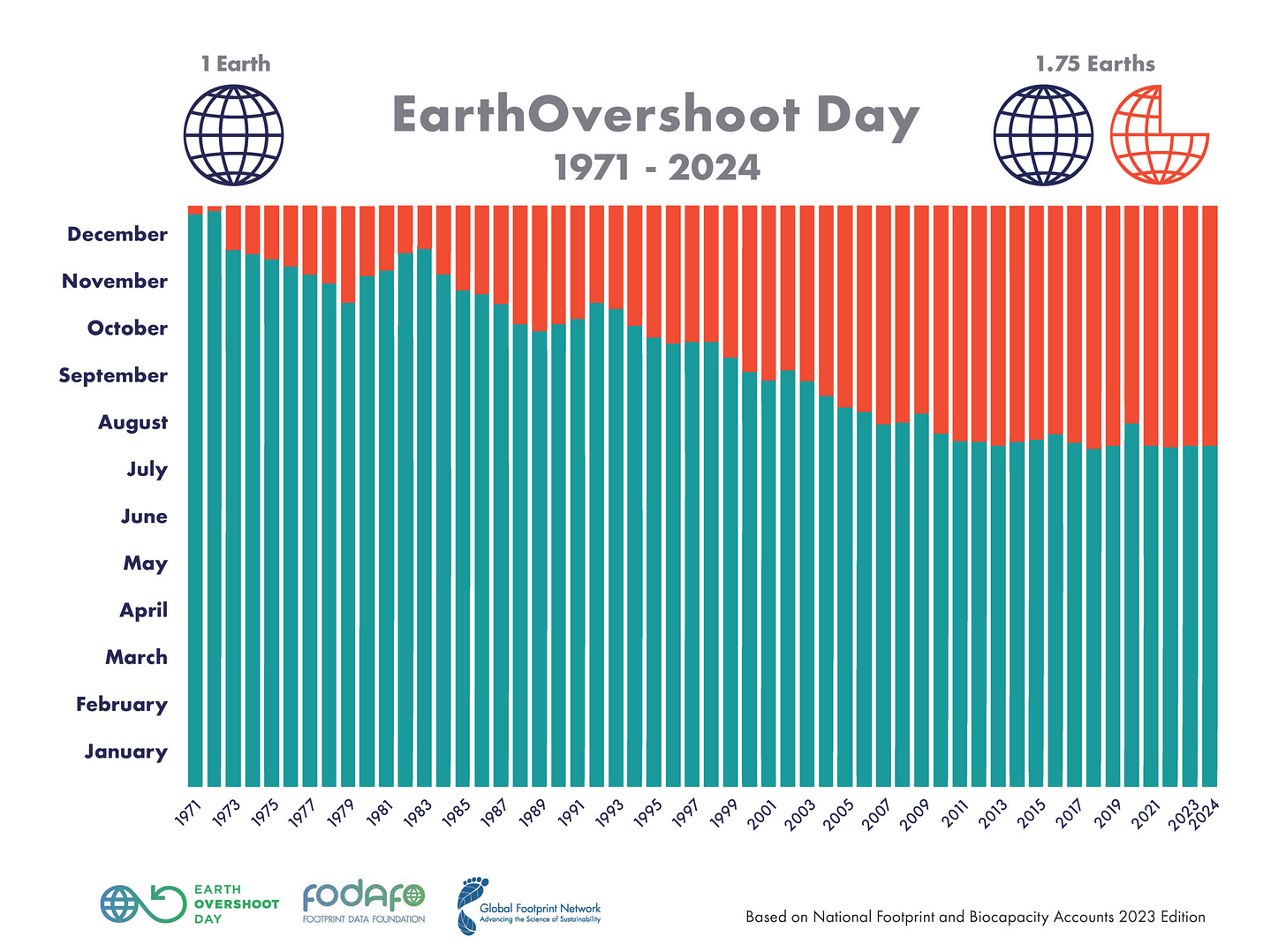

In fact, this year Earth Overshoot Day occurred as early as August 1st! This means that in seven months, we used everything our planet can regenerate this year. We are currently using nature 1.7 times faster than our planet’s ecosystems can regenerate.

Something has to give!

We need to rapidly take action to reverse these dangerous trends. But where are efforts best placed? Understanding what demographics contribute the most to planetary boundary transgressions is a good place to start, as doing so helps to identify where the biggest levers for change are.

Are the planetary boundaries crossed evenly?

So, we know that planetary boundaries are being crossed, but who are the main culprits? Where are these transgressions coming from?

A new study by Tian et al. in Nature provided insight into the contribution of different income groups across the world.

Several studies have identified affluent countries, such as the USA and countries in the European Union as being the key culprits for planetary boundary transgressions, but these overlook within-country differences between rich and poor, and the potential role of affluent individuals in poorer countries.

To overcome these issues, Tian et al. used an expenditure database of consumption groups across 168 countries to study the impact of spending patterns on six key environmental indicators.

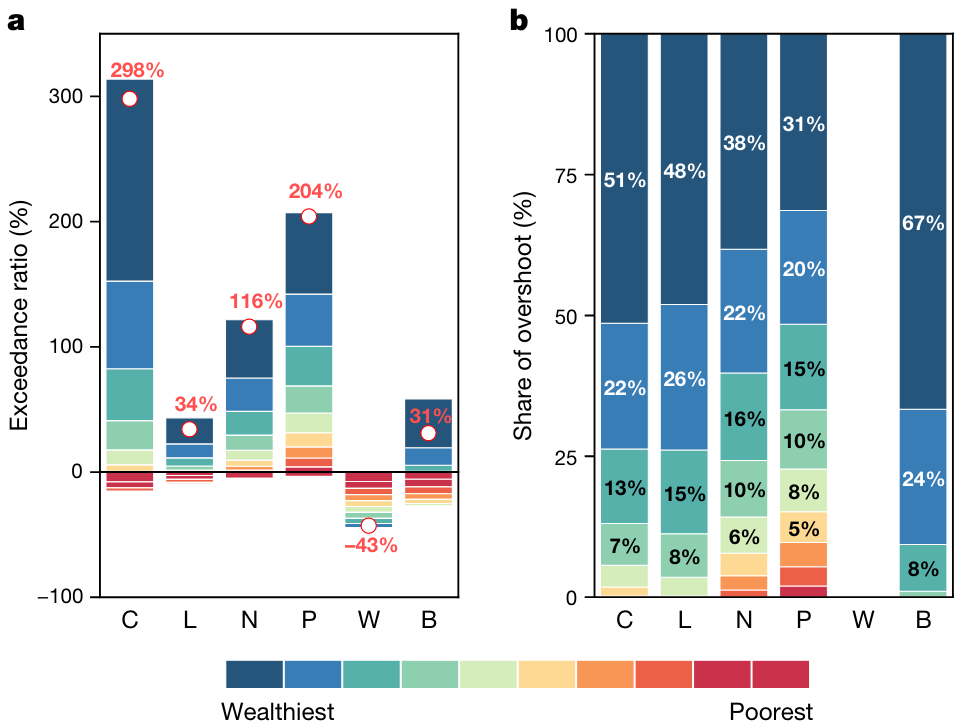

In short, affluent consumers are responsible for planetary boundary overshoot. They found "31–67% and 51–91% of the planetary boundary breaching responsibility could be attributed to the global top 10% and top 20% of consumers, from both developed and developing countries".

The numbers are staggering, but unsurprising. Forty three percent of carbon emissions came from the world's wealthiest 10% of consumers. Similarly, 23% of human appropriation of net primary productivity (an indicator of land-system change), 26% of intentional nitrogen fixation, 25% of phosphorus fertiliser use, 18.5% of blue-water consumption, and 37% of mean species abundance loss were due to the top 10% of consumers.

To really hammer home the inequalities here, the poorest 10% contributed a maximum of 5% to any of the six indicators.

Overall, the richest 10% exceeded all per-capita planetary boundary thresholds, ranging from 110% for freshwater use to 1700% for climate change (CO2 emissions). By contrast, the poorest 10% remained well within all boundaries. These discrepancies were even preserved within affluent nations like the USA (but I won't delve into country-level differences here).

As you can see in the figure above, the richest ten percent's share of the overshoot is substantial. Almost 70% of biosphere integrity declines (mean species abundance declines) is due to the top 10% of consumers. At the global scale, only one of the six indicators stayed within the planetary boundary (freshwater use). The remainder overshot the boundary by between 31% (biosphere integrity) and almost 300% (climate change).

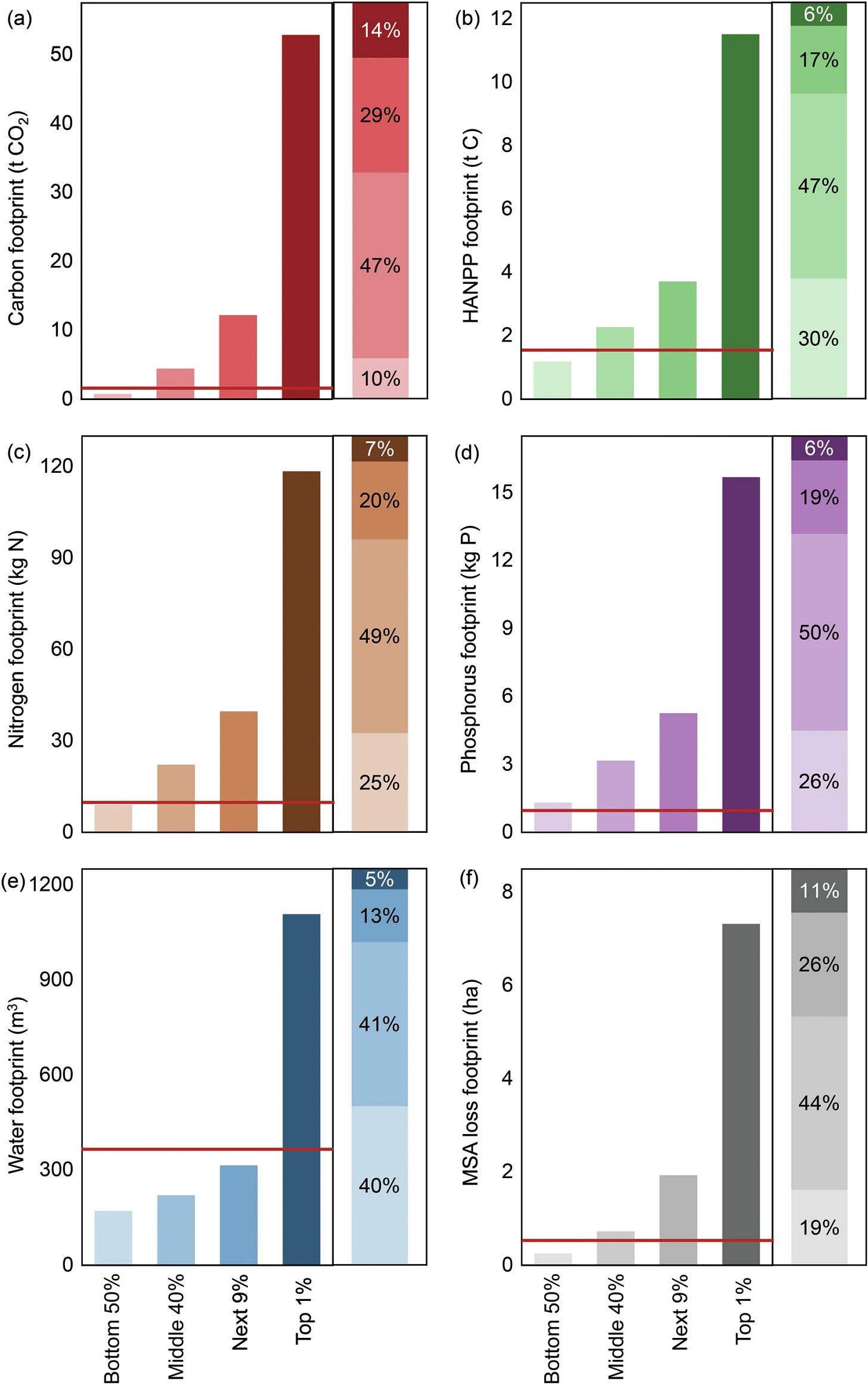

As you can see below, the differences even between the top 1% and the next 9% are staggering in their footprints of the six indicators. And the share of the total footprints is equally staggering. The top 1% of consumers contribute 14% to carbon footprint and 11% to the species loss footprint.

What can we do?

The study by Tian et al. (2024 Nature) uncovers extreme inequality in environmental footprints. Affluent groups are contributing disproportionately to planetary boundary transgressions, in both developed and developing countries.

As I said earlier, though, what is most exciting about this work is the uncovering of potential mitigation pathways. Knowing where the big contributions are coming from helps to identify potential levers of change.

The authors go on to simulate what reductions in consumption by the top 10% and 20% of consumers would do to alleviate environmental pressures. In short, it would do a lot. Changes to the services sector and the food sector appeared to be the best levers to pull to exert the biggest impact on reducing environmental pressures from the wealthiest consumers. Efforts to both reduce consumption and improve efficiencies within high-end consumers are key.

More specifically, they found that:

"the global top 20% of consumers could adopt the consumption levels and patterns that have the lowest environmental impacts within their quintile, yielding a reduction of 25–53% in environmental pressure. In this scenario, actions focused solely on the food and services sectors would reduce environmental pressure enough to bring land-system change and biosphere integrity back within their respective planetary boundaries."

The key point for me is that, while the most affluent people have an outsized impact on transgressing the planetary boundaries, they also have the largest potential to have a positive impact.

Clearly, then, we need to focus on high-expenditure consumers. Without changing their behaviour, effectively addressing our overshoot of planetary boundaries will be much more challenging.

But what I found most exciting with this study is that we don't have to convince the wealthy to return to caveman lifestyles, we just need to convince them to be a bit more moderate in their consumption.

What do you think? I'd love to hear your thoughts. How does this sit with you? I’d love to get a discussion going on this one!

Oh, and hey, on a more positive note, holiday season is upon us! How about you gift a friend a subscription to my newsletter? It's all free anyway, but, you know, you're gifting the chance to have something to chat about together over the holidays. :) And you can always gift a paid subscription if you're feeling particularly generous!

I've sort of obsessively been paying attention to the dumping of used clothes in Accra Ghana. PBS News Hour has featured some great journalism in partnership with Undertold Stories. I had no idea that the Western thrift clothing "industry" works with middlemen to export unwanted clothes that end up being purchased in bulk by clothing sellers in Accra's markets. The quality of clothing is so poor that most of it gets burned or dumped in the water. Just highlighting the clothing industry as another place where conspicuous consumerism is pushing microplastics and pollution on to poorer countries... If we can curb consumerism here, we should be figuring out better recycling options. One social enterprise in Accra is making particle board for building materials out of the dumped clothing. But as much as they take off the beach, it shows up and more then next week.

This was a very interesting topic to write about and no surprises about the wealthy being the biggest contributors to environmental pressures. The trick, as you say, is to get the wealthy on board with changing their behaviour and also contributing financially to projects that can reduce climate issues. Instead of Amazon donating $1.7million NZD to the Trump inauguration ceremony wouldn't it be better that the money was spent helping to reduce climate issues.