Extreme floods continue to batter the world

And they're set to continue to intensify with climate change.

In June 2021, a large low-pressure mass built up over the Tasman Sea to the west of New Zealand before proceeding to pick up moisture-rich air from the Pacific Ocean to the north and slamming into the east coast of New Zealand’s South Island.

This event caused widespread destruction across the Canterbury region of New Zealand, with many of the large rivers draining the eastern slopes of the Southern Alps flooding, damaging critical infrastructure and putting lives at risk.

Although this was described as a one-in-two-hundred-year event, the reality of climate change means these kinds of events will recur at much higher frequencies than in the past.

In the weeks that followed this event, we witnessed catastrophic floods unfolding elsewhere in New Zealand, as well as across Europe and China.

The recent devastating floods in Valencia, Spain, where year’s worth of rain fell in eight hours and more than 200 people died, have brought these issues to the fore once again.

painted the picture of this nicely:"The torrential downpour swept away bridges and buildings and left a trail of devastation in its wake. Residents report seeing people desperately climbing onto car roofs as a tide of muddy water surged through streets. Emergency services footage shows the extent of the destruction, showing collapsed bridges and vehicles piled atop one another."

Isn't it horrible to see such widespread destruction?

Such events serve as a reminder that the main way in which humans will feel climate change is via increasing frequencies of what we currently consider extreme events.

We continue to see records being broken in terms of heat across the globe, with July 2024 the 14th consecutive month of record-high global temperatures. A warmer world is a more extreme world. With increasing averages, comes increasing variability.

‘Worst flood in modern history’ statistics seem to be business-as-usual these days.

It doesn't stop at floods either. Over recent years, we have seen increasing frequencies of various extreme climatic events, including high profile drought and wildfire events across western North America and eastern Australia. These events have caused tens of billions of dollars of economic damage, severe losses of biodiversity, and loss of human life.

Unfortunately, climate change-driven disturbances are predicted to continue to intensify by more than an order of magnitude over the next 100 years.

Let’s look at floods in particular.

Floods are intensifying and projected to continue to do so

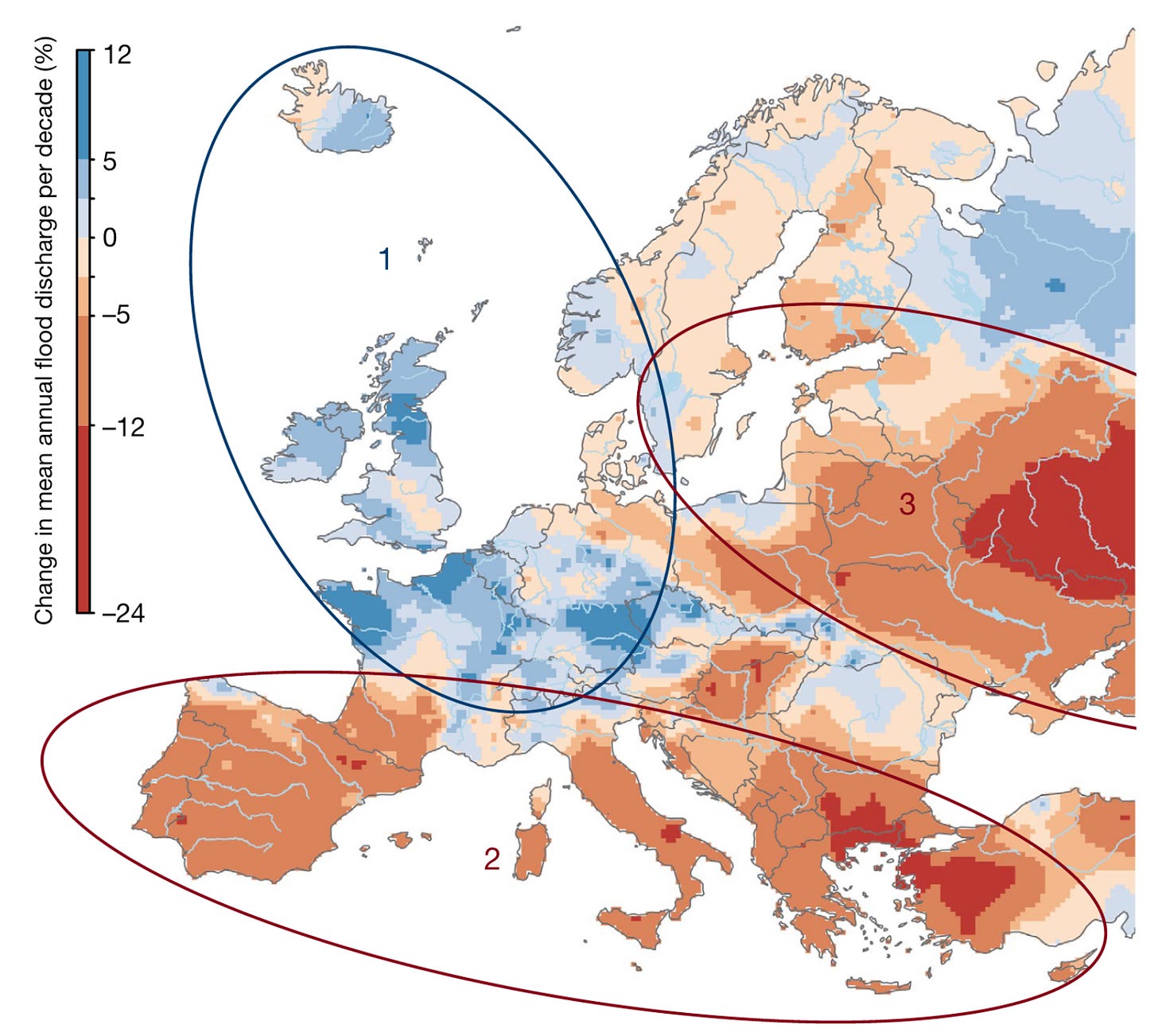

Changes to the climate have already translated into increased flood magnitudes across the world. For instance, research examining regional trends of flood discharges across Europe between 1960 and 2010 uncovered considerable changes across the continent, but these were geographically unique:

"Our results—arising from the most complete database of European flooding so far suggest that: increasing autumn and winter rainfall has resulted in increasing floods in northwestern Europe; decreasing precipitation and increasing evaporation have led to decreasing floods in medium and large catchments in southern Europe; and decreasing snow cover and snowmelt, resulting from warmer temperatures, have led to decreasing floods in eastern Europe." (Bloschl et al. 2019).

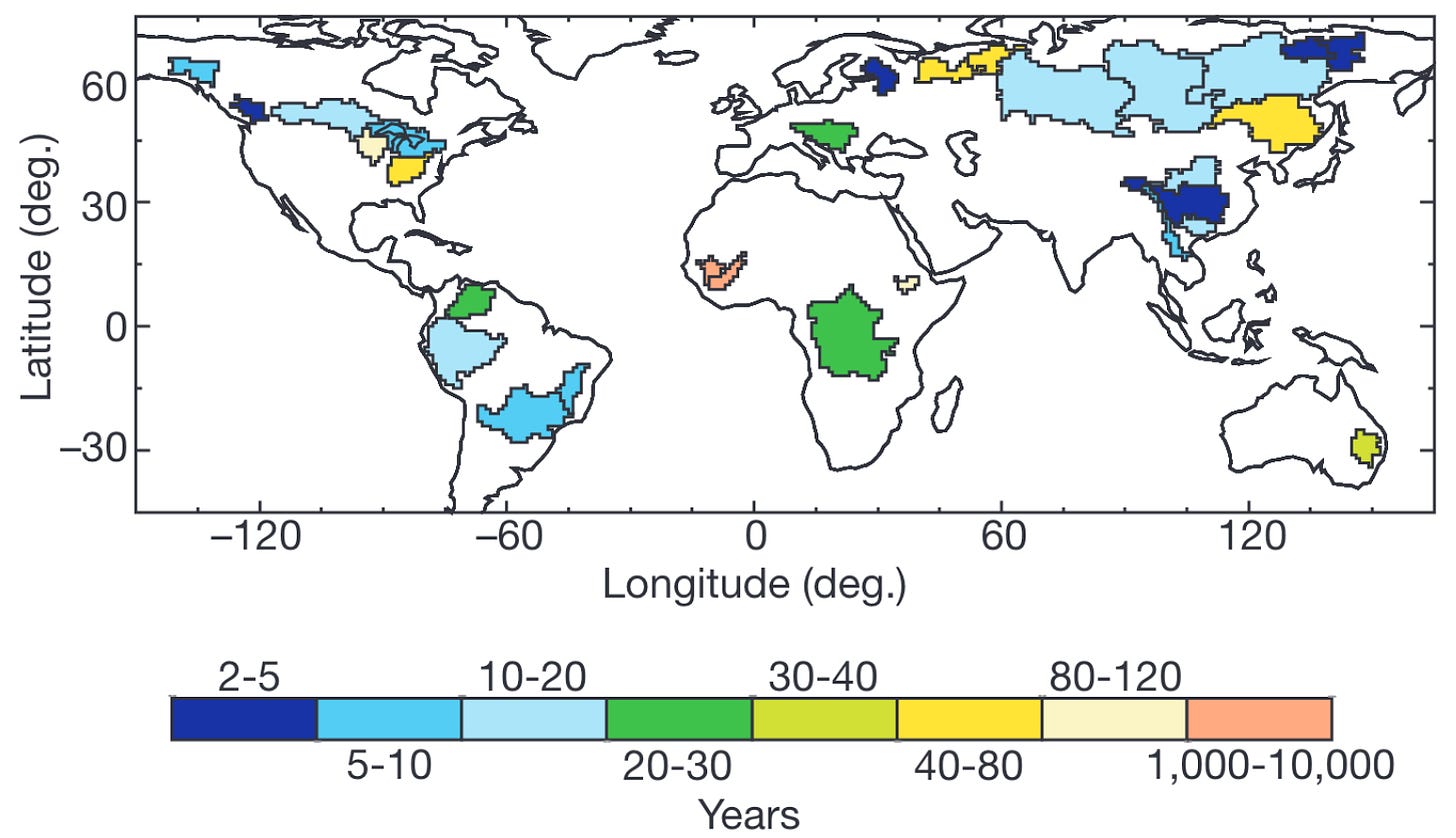

And floods are projected to further intensify with ongoing climate change. For instance, the risk of great floods (those with discharges exceeding 100-year levels from large river basins) increased substantially during the twentieth century. Models suggest the risk of these great floods is predicted to continue into the future.

Specifically, this research showed that climate change (via changes in CO2 in the model) is predicted to increase the frequency of 100-year return interval floods in all but one large river basin in their global study. Half of the basins are predicted to see dramatic changes, with a predicted decrease in return period from 100 yr to less than 12.5 yr.

Any changes in river floods threaten the design of flood protection measures moving forward. As I stated in an earlier post, we have entered the age of nonstationarity. So we can no longer rely on the assumption that river flows operate within known bounds. Instead, we have to think about new ways of designing water infrastructure to protect our populations.

Yet, the number of people exposed to floods is increasing. Research has estimated that the number grew by 58–86 million from 2000 to 2015 and this is predicted to increase further.

The threats to human infrastructure are clear. More nuanced, however, are the threats to freshwater biodiversity and to the ecosystem goods and services provided by rivers.

Ecological impacts

Extreme flood events can unsurprisingly have extreme ecological impacts. But the challenge with extreme events, is the fact that they are rare by definition. So opportunities to study them are rare. And as a result, evidence of their impacts isn’t overly abundant.

Often studies on the impacts of extremes are opportunistic. For instance, a researcher might have an ongoing study that is impacted by a flood and they pivot the focus of their research to study the extreme event instead. Alternatively, as we did recently, a researcher may be well positioned due to chance to capitalise on an event. We had studied a set of streams in the Canterbury region of New Zealand for a different purpose before a major weather event hit (the project was focused on the interactive influences of flow alterations and non-native trout on vulnerable galaxiid fishes). We happened to have a fantastic student at the ready to opportunistically study the impacts of this extreme flood event (in the presence of trout) for their Master's research. The result was an understanding of how trout modify the recovery of native fishes from flood events. (Caveat: neither of these studies have been through peer review yet.)

But it’s rare that researchers are in such positions, particularly due to the difficulties in sourcing funding and the fact we can't predict when they'll occur.

To make matters more challenging is the fact that responses to extreme floods tend to be idiosyncratic. But mostly, their impacts are multifaceted and can depend on the scale of the event (e.g. floods hitting a single headwater stream vs. a whole catchment). While streams impacted by small-scale events can be recolonised by species living in nearby parts of a river network, more extensive floods can take much longer to recover from. And recovery, of course, also depends on how much a river gets moved about during a flood. (River geomorphology—the physical structure of a river—is largely strongly controlled by flood events.)

I'll save a deeper dive on the ecological impacts for a later date, but suffice to say they are varied and wide ranging, including altering the genetic structure of populations that inhabit impacted rivers, complete reorganisation of the types of species inhabiting a river, changes to the way a river performs critical functions like cycling nutrients or breaking down organic matter, and even providing new opportunities for invasive species to invade and outcompete natives.

Two specific types of events are particularly concerning to me, however. First, compound extremes (e.g. droughts followed by extreme floods or even multiple floods back-to-back) can have particularly major impacts. Floods that hit an already recovering system can be particularly impactful. Even if the flood event isn't extreme in magnitude, it can be in impact in certain circumstances. For instance, a study in New Mexico, USA, found floods that followed a catastrophic forest fire led to major reductions in water quality that persisted for 50 km downstream, threatening water supplies to cities and agriculture. Second, just like compound extremes interacting stressors can intensify the impact of extreme floods. For instance, extreme floods can have greater impacts in regions that have been subject to widespread land-use change. Changing land use can alter the patterns of runoff, leading to more intense flood peaks, particularly in urban areas.

Where to from here?

Climate change is altering the global water cycle. Extreme floods, droughts and heatwaves are set to increase in their severity and regularity with continued climate change. Limiting the damage will require drastic and immediate action from governments. But they’re not moving fast enough.

In future posts, I'll cover some of the ecological topics I've briefly touched on here. And I'll also return to discussing some more of the levers we have at our fingertips for managing extremes. (If you’re interested in rivers, I wrote a post a couple months back on giving river ecosystems a chance.) Extremes present major challenges to policymaking and management, because of the uncertainty they come with. But there are frameworks available that are useful in this context.

If you enjoyed this post, please click the ❤️ button to help more people discover it. And tell me what you think in the comments!

Do you know someone interested in environmental issues, climate change, biodiversity, water management? Forward this newsletter to them!

Speaking of not moving fast enough, COP16 is now finished.

nicely summarises the outcomes here. Among some good progress in certain areas, there continues to be too little, unfortunately. Once again, the world is kicking the can down the road.Note, much of the introductory material is copied and modified from a book chapter I published in 2022:

Tonkin, J. D. 2022. Climate change and extreme events in shaping river ecosystems. Pages 653–664 _in_ T. Mehner and K. Tockner, editors. Encyclopedia of Inland Waters (Second Edition). Elsevier, Oxford.

Some related reading:

Welcome to the age of nonstationarity

In 1922, commissioners from seven states met to apportion water from the Colorado, the largest river in the southwestern United States.

Give river ecosystems a chance

Freshwater makes up somewhere in the order of 1% of the Earth's surface. Despite this, freshwaters harbour around a third of all…

Your article about extreme flooding was very interesting, especially in light of the recent flooding in Spain. I recently read a book by Jeff Goodell called The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities and the Remaking of the Civilized World. Although he talks mainly about the effects of sea level rise, he delves into the human aspect of how we react (or not) to flooding events and potential loss of land attributed to sea level rise. Reading this book and your article reminds me why we have to work harder to address climate change.

https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/extreme-downpours-increasing-in-southern-spain-as-fossil-fuel-emissions-heat-the-climate/