Are win-wins possible in complex environmental management?

Tradeoffs rule the world

Think back to the last time that you made any sort of decision. Something had to be selected at the expense of something else, right?

That's what decisions are. It's very rare that a decision doesn’t come with some sort of consequence. Even if it's not immediately obvious, tradeoffs are at the heart of every decision.

Choosing one option inherently means rejecting or delaying others, which could result in missed opportunities or different outcomes. That's why decision making is so taxing. It requires giving something up and that may be something you value highly.

So, what about decisions around managing the environment? There's always going to be tradeoffs, right? Every decision for one thing is a decision against another thing to some extent. Or is it?

I've said many times in this newsletter that there is the possibility of win-win biodiversity-climate solutions. That is, that there can be measures or actions that benefit both biodiversity and the climate simultaneously. Not all climate mitigation strategies have to be free of consideration for biodiversity.

But if a decision for one thing is a decision against another, how is that possible? Surely something is being traded off.

Let's first look at this with some examples from managing river flow regimes (sequences of floods and droughts that rivers experience).

Tradeoffs in river flow management

Rivers have been modified around the world through the building of dams. These dams, which are built for hydroelectric energy generation, irrigation or drinking water supplies, can considerably modify the flow regime downstream. This might be by removing any of the natural floods and droughts that system experiences all the way through to massive daily fluctuations in water flows to generate electricity in response to energy demands (think about when you wake up and turn on all your appliances — this energy needs to come from somewhere; we call this hydropeaking).

Organisms living in or alongside rivers like fish, invertebrates or riparian trees evolved over thousands of years to cope with and capitalise on these natural rhythms. Change them in any way, like changing the timing of the flood pulse or adding small flood peaks during fish nesting season, and there will be repercussions for the biodiversity in that system. And there is widespread evidence of the detrimental impacts of flow modification on freshwater biodiversity. (A topic for a future post.)

So, it's clear that modifying river flow regimes is consequential for biodiversity.

One thing we do to mitigate some of these impacts is to design what we call environmental flow programmes, where dam-modified flow regimes are redesigned to optimise for something downstream while continuing to deliver on the dams primary objectives such as power generation.

What's that I hear you say? "Jono, that sounds like a tradeoff!" Why, yes it is!

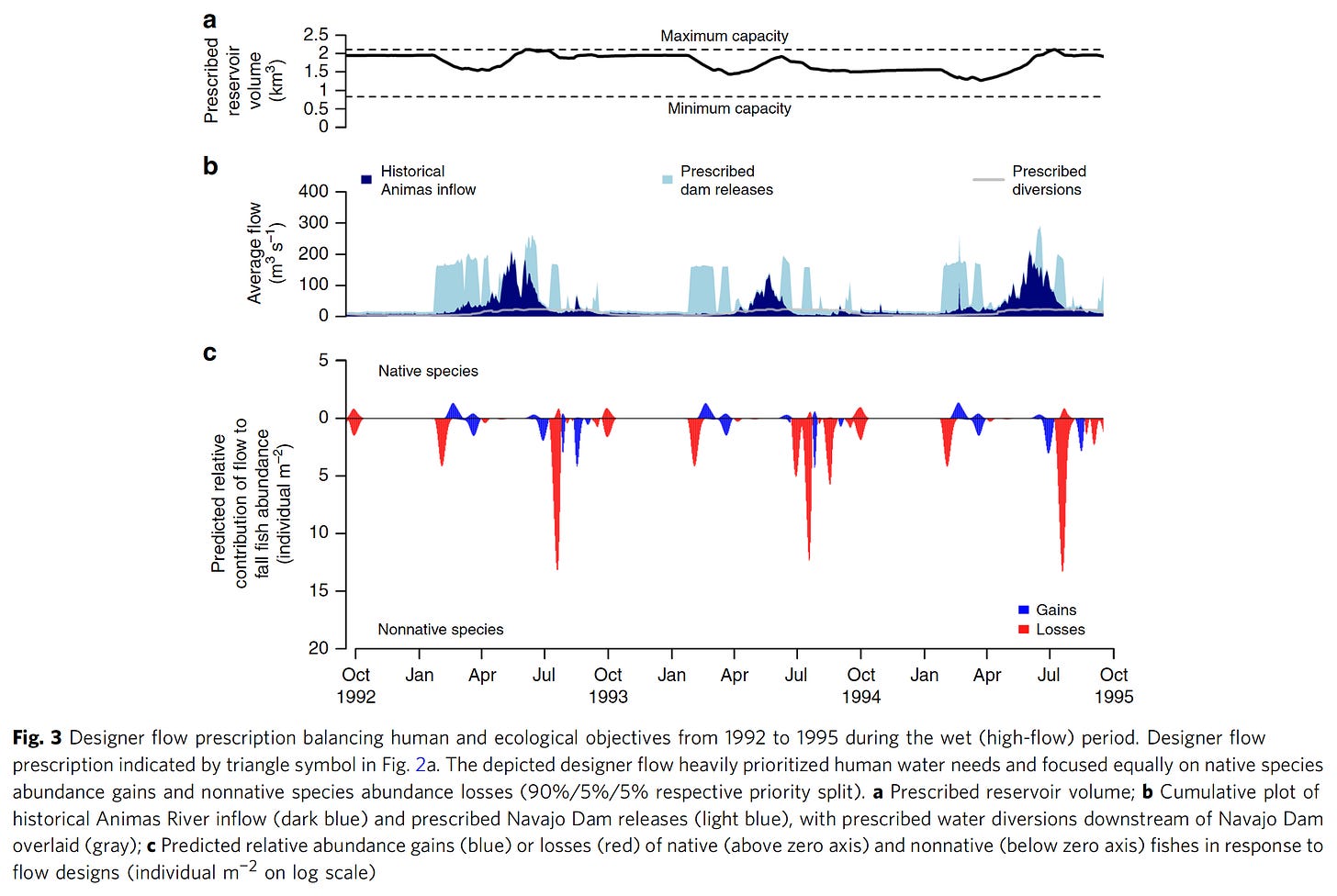

We can do some cool things here to design flows that balance these tradeoffs. One excellent paper from a friend of mine designed river flow regimes in a southwestern United States river that balanced human water needs with the dual conservation targets of benefiting native fishes while hampering nonnative fishes. They were able to work within a pre-defined set of conditions that delivered human water needs of the system while targeting flows that removed nonnative fishes and benefited natives.

So, it's possible to manage flows that meet human and environmental needs, but there are tradeoffs to be had. These are not optimal for either goal. But as you can see in the figure, you can cleverly manipulate flows to deliver on multiple targets, not just human needs.

One thing that struck me in environmental flows research was that the target of managed flows is often one component of an ecosystem, such as native fishes (above) or a single species of riparian tree (e.g. often cottonwoods in the US or river red gum in Australia), while overlooking other components of an ecosystem. (Obviously, it's hard to prioritise everything in a system.)

I was dissatisfied by this, as it stands to reason that targeting any one member or sector of an ecosystem will likely come at a cost to other members of the ecosystem.

So back in my time in the States, I initiated a computer modelling study looking at the tradeoffs among river flows designed to benefit different components of the ecosystem. That is, what happens to the rest of the ecosystem when we prioritise flows designed to benefit cottonwood over other riparian trees? What about native fishes? What about flying insects (those that emerge for part of their lifecycle)?

What I found was that targeting any one sector of the ecosystem often had major consequences for other sectors. This is because, for instance, cottonwoods benefitted most from large floods every few years, but this hampered native fishes, which require regular flood events that they use as spawning cues or dispersal triggers. Unsurprisingly, the historical natural flow regime was most beneficial for the whole ecosystems. As you can see (figure below), the natural flow regime comprised a combination of the three frequencies and magnitudes of flow events that the three targeted 'designer' flows comprised. Each targeted group performed slightly worse under natural conditions, but not far off its optimal. Again, this makes sense, the biodiversity that inhabits a river has evolved over thousands of years to work with the natural signal it experiences.

It's difficult to describe this in a brief paragraph, but suffice to say, there are tradeoffs involved with designing flow regimes for any narrow target.

So, from these examples, it appears there are no true win-wins, but there are healthy compromises.

What other evidence is there?

Are win-wins possible in environmental management?

It is widely asserted by academics that win-wins are possible in research on environmental management decisions (guilty as charged). Practitioners are less convinced by this argument due to lived experiences.

For instance, there have been major global studies that have suggested large-scale win-win outcomes in environmental management, including projections of a possible increase of 50% of global crop yields while halving fertiliser use.

Another showed that rebuilding global fisheries could also provide co-benefits for threatened marine mammals, turtles and birds. They projected that maximising fishery profits would halt or reverse declines of approximately half of these threatened populations.

These are big things with big consequences. But often they overlook other tradeoffs that aren't incorporated into decision making.

The reality of the situation is that when things get complex, the chances of finding win-wins reduces. A recent study demonstrated this nicely mathematically. They showed that the more objectives there are, the more stakeholders there are, or the more constraints there are, the less likely you are to reach a win-win (and the more severe the tradeoff).

So, the evidence is mounting that true win-wins are rare.

But what about for climate solutions? Are there climate solutions that also benefit biodiversity?

To me, when it comes to finding solutions for biodiversity loss and climate change, I believe win-win solutions are possible but these don’t come easy.

In short...

… tradeoffs rule the world, but win-wins may be possible

Currently, many of our efforts to mitigate climate change can be detrimental for biodiversity for reasons I have discussed:

"climate fixes like planting monocultures of fast growing trees for carbon capture can have detrimental biodiversity effects for a number of reasons, including planting in areas that were not previously forested leading to increased fire risk or loss of native species and associated ecosystem functions."

This is an unacceptable tradeoff.

It's imperative we avoid these win-lose situations, where we prioritise one at the expense of the other. Instead, when it comes to the joint biodiversity-climate challenge, it's important to tackle the two together as there are absolutely possibilities to find synergistic benefits.

Nature-based Solutions or Natural Climate Solutions are a key example of where win-wins are possible, as I've discussed previously.

"Green infrastructure is one such example. Cities are set to get hotter and harder to live in if climate projections are to play out. Green infrastructure like tree planting in parks, on streets and along waterways will help to reduce the heat island effects cities will experience. It will also contribute to climate mitigation goals via carbon capture, come with multiple ecological co-benefits such as providing habitat for native species, shading waterways and provision of organic matter for detritivores, and provide many well-known social benefits."

As I'm sure is clear by now, there are tradeoffs with every decision — it's just where those tradeoffs occur that is the important point. In the case of choosing between climate and biodiversity targets, that's asking the wrong question. We should be choosing both together, while searching for synergies among them.

If they come at the cost of unfettered economic growth, that's an acceptable tradeoff to me.

What do you think? I'd love to hear your thoughts. Don't forget to like the post and share with your friends — I'm keen to spread the word on these issues.

If you're new here, check out the archives.

A couple of relevant posts:

Win/lose situations happen a lot when people jump at an easy solution that gets an immediate problem off the table and makes everyone feel like they’re doing something good but without tackling any complexity - just plant trees, many recycling systems, electric cars are obvious examples.

A problem with the SDGs is that it is easy to pick the one or two that you are interested in and ignore the rest. That’s why I prefer Doughnut Economics.

I think win/wins are possible with genuinely diverse networks and well-managed collaborations. Not easy but possible. Both SDG17 Partnerships and Doughnut’s networks appear to recognise this.

It's a shame we have to have these trade offs in our natural world in the first place but that is the world we live in. However, your article gives me hope, by bringing awareness and possible solutions to the forefront can only create more awareness and therefore more solutions from a wide range of sources.